Live performance is the income stream for the artist that often offers immediate financial benefit to the new artist, and it provides a continuous and steady income for the established artist. The other primary income sources for artists are various royalties from songs they have written, the sale of their recordings and related products, sale of merchandise, and the acquisition of sponsorships and product endorsements. Self-managed artists can receive performance royalties when they play their own music in small clubs and other venues, from the three Performing Rights Organizations (PROs), though this a smaller amount of income. We’ll discuss that in detail in Chapter 10. The focus of this chapter is managing the artist’s live performances.

We live in a world of digital entertainment that makes any music a fan wants available any time they want it, and anywhere they want it. You name the device, and it’s available—which is why live performance has become so valuable to an artist. A live performance is where the artist and the fan can share the same space for two hours, and each can have an experience that will never happen the same way again. It is special. And the only way to have that experience as a fan is to make the time for it and buy admission to the performance.

Live performance is the income source that has the greatest number of elements that require the personal involvement of the artist manager, but live performance in the United States is an area of the music business that has thrived and grown even through times that included an attack on a major U.S. city, war, and the deepest economic recession ever. The data from annual January issues of Pollstar magazine, shown in Table 9.1, clearly demonstrate that live performance is an area of the artist’s career that holds opportunity.

Earning money from live performances is often the most immediate way that an artist can begin to support a career, and it is for this reason that it is so important for the manager to understand it and to exploit it for the benefit of everyone who is part of the business support group. It is an important way for the artist to build a fan base, to develop professionally, and to sell recordings.

There are five principal job areas that support an artist who will be earning from live performances: booking engagements, managing the tour, promoting the tour, managing the administrative business functions, and generally managing the artist. Figure 9.1 shows the relationship of these functions in the live performance hierarchy.

A manager of a small artist management firm often performs some or all these duties. In larger management companies, they are divided into functional areas of an artist’s support team, with individuals having these specific responsibilities.

There are two types of tickets that an artist will sell: soft tickets and hard tickets. Soft tickets are those that are purchased by fans to attend events where an artist is a participant with other artists at events like festivals and fairs and megamusic conferences like the Brighton Music Conference in the UK and South by Southwest in Austin, Texas. Soft tickets are also those provided to casino patrons for artist performances. From a management perspective, soft tickets help generate an occasional revenue stream, but for the long term, selling hard tickets is the objective. Hard tickets are those that fans buy to specifically see the artist. It’s important that the artist develops a following that is interested in seeing them on a regular basis and willing to pay to specifically see the artist perform. The manager should make this a priority, because it creates an income stream that is specific to the artist and pushes the artist to build the confidence to become a headliner.

FIGURE 9.1

Concert hierarchy.

As you learned in Chapter 6, the agent is responsible for finding opportunities for paid live performances for the artist. The typical payment made to booking/talent agents is 10% of the contract value for booking a concert tour into a series of venues. The “contract value” isn’t based on the price of the ticket to the performance; rather, the contract value is the amount paid to the artist to agree to perform, and the agent earns commission on that amount. Ten percent is the standard charge by agents who are franchised through the American Federation of Musicians and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. It is sometimes possible to negotiate a lower fee, such as when there is a series of performance dates with the same promoter.

Agents and managers multiply the commission rate times the commissionable income relevant to their responsibilities. A manager often defines commissionable income as the gross income of the artist. However, a booking agent only gets a commission on what the artist is paid for the shows that the agent booked—not actual gross.

(Barnet 2014)

There are agencies that specialize in booking performances in small clubs with 100–200 seats, as well as weddings and corporate events. Often they book scores of artists and are especially good for new artists or for those who do not want to rely on music to completely support their lifestyle. For the manager of a new client who needs seasoning in a live performance setting, small agencies like these can provide access to a range of smaller venues and performance settings that allow the new artist to take some chances in environments that frequently overlook mistakes. Commissions to agencies that book small venues and performances may be higher than 10%, because the value of the performance contracts is relatively small. When an offer from a promoter is accepted by the manager and the contract is signed, the agent collects a deposit or “guarantee” from the promoter with specific instructions regarding when additional payments must be made to the artist. For example, some performance contracts require a deposit with the signed contract and an additional percentage payment of the agreed amount 30 days before the engagement.

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT OF LIVE PERFORMANCES

Among the decisions artist managers—whether contract managers or self-managed artists—must make is determining if it is better to assign the business management of live performances to a business manager or to do it themselves. Either way it is handled, the artist manager must make a determination about whether an available paid performance or a series of tour performances will earn enough money for the artist to make the bookings worth accepting. The manager notes how much the performance will pay the artist and subtracts all expenses associated with the engagement. The result, or the net, is the amount that would be earned by the artist if they accept the offer.

There are some performances that may have promotional value to the artist, and the manager and artist might agree that breaking even is a good result. Breaking even means that the payment received for the performance and the expenses associated with it are equal, and the artist makes nothing. An example of when a breakeven performance might be practical is when an artist has the opportunity to open for a headliner, knowing that the appearance will be helpful in promoting a recording, attracting the attention of radio, or building a fan base.

Budgeting for performances requires considerable planning by the business manager or the artist manager. A detailed listing of all costs of a live performance must be compiled. Overlooking one component of it could be the difference between making money or losing money, and the novice artist manager or self-managed artist who does not have a strong background in bookkeeping or accounting should seek advice from an entertainment business manager. Anticipating expenses from live performances and budgeting for them is a skill that comes from the experience of doing it and living with the results. For performances that are booked with a promoter in which the artist and promoter will split the profits, the promoter will present a proposed budget to the artist manager through the booking agent before a contract is signed. However, for a performance that pays a flat guarantee to the artist—an amount the artist is paid regardless of how many tickets are sold by the promoter—does not require budget approval because the promoter is taking all of the risks associated with the show.

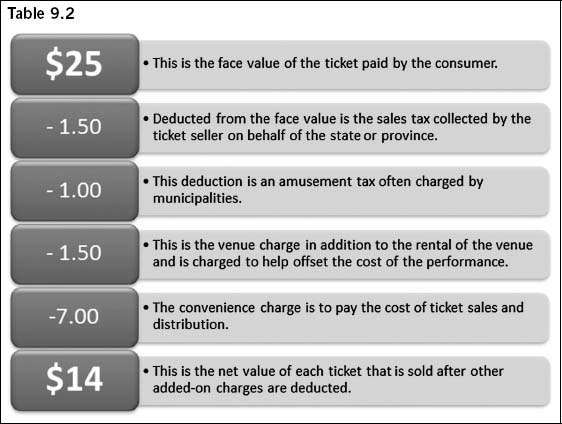

When creating a budget for performances that require tickets, it is important to consider what charges the ticket price includes in order to determine how much of the price actually goes toward paying the cost of the performance. Table 9.2 shows how a $25 ticket might actually be worth only $14 to the artist or the promoter before the bills are paid. And it is essential to keep up with current taxes in the state or province where an artist performs. For example, municipalities that learned lessons from the 2007–2009 Great Recession are increasing local taxes and some are now adding fees called “first responder fees” and “admission surcharges” which are merely euphemisms for taxes.

So when estimating the income from the sale of tickets, it is important to use the net amount from total ticket sales, which is the total the performer will receive after all expenses have been. Be careful that you do not budget a performance based on the gross amount the artist receives from ticket sales. Additionally, the budget must take into account exchange rate differences between countries; for example, “dollars” in the United States and Canada are not the same.

When an artist splits the profits with a promoter and plays a ticketed venue that has different tiers of seating (the upper-tier “nosebleed” section versus the front row), it is important to have the business manager check the budget figures of the promoter to be sure that the projected income based on demand for each different ticket price is reasonable and accurate. Creating different ticket prices for different seating areas is something promoters refer to as “scaling the house.”

If the artist has a recording contract with a large record company, it is possible to negotiate an amount of money in what is called tour support. This is money that is given to the artist to offset losses artists incur while they are touring to promote single or an album for the company. When the budget is prepared, the manager presents it to the record company, noting how much money the artist will lose while on tour. The money the artist will lose is the basis for the amount of tour support money the label will advance to the artist. Tour support money may be offered by a major record company in a range of $25,000 to $100,000, but in every case the artist must repay the money to the company through recoupment. Although advances to an artist are typically commissionable for the artist manager, this is an advance that is not one the manager can draw from. Record companies view tour support as a promotional expense rather than a payment for services, and do not permit managers to draw commissions from them (Passman 2012).

The current view of tour support by labels is that it is an investment with intended results in either the sale of recordings or getting the attention of radio. Tour support is no longer a standard commitment to an artist; rather, it is offered to artists when the label feels there is a potential for a “big payoff” and they sometimes will provide substantial sums to support touring (Dungan 2007). New artists who open for established acts effectively earn nothing directly from their performances, so tour support becomes important to them to help offset expenses they can’t recapture. Likewise, tours planned for foreign countries often require tour support because of the added expense of logistics.

A budget for performances and tours should also include any amounts committed to an artist by a sponsor. Where it is possible, the artist manager should urge sponsors to provide their financial support before the tour begins. The early receipt of this income is helpful in building the show and assembling the physical assets that are necessary to accompany the artist on the road.

The artist manager or someone on the manager’s staff must handle the activities of managing a tour. As an artist becomes more active touring and the manager cannot be with the artist at every performance, it becomes necessary to hire a tour manager. This person is effectively an extension of the manager while the artist is on the road, a position that requires someone with patience, an orientation to details, and an understanding of human nature. The tour manager, sometimes referred to as a road manager, is the primary contact for everything while the artist is touring, and is totally responsible for getting the artist to a performance and ensuring that the performance is presented without any problems.

The tour manager takes primary direction from the artist manager, and then creates a detailed itinerary, beginning with the departure from the home base for the first show on the first date. When the artist manager has approved the itinerary, the tour manager begins finalizing the travel schedule, chooses and confirms the mode of travel, and reserves overnight accommodations. To organize each stop, the tour manager will use a template similar to the following list:

Date of performance

City, state, province

Name of venue

Name and contact information of promoter

Directions to the venue

Time to load-in equipment

Time for sound check

Time doors for audience open to enter the venue

Time the performance begins

Length of the performance

List of guests

List of merchandise for the event

Copy of technical rider

Copy of the performance budget

Catering for artist and other performers

Confirm equipment rental

Confirm hiring of stagehands and others to support the performance

Create “day-sheets” for each stop for artists which include call times for rehearsal, performances, information about local amenities

It’s easy to see how an artist manager can quickly become overwhelmed by the necessary support for even a small tour. Each of the activities listed in the chart requires a number of telephone calls and emails, and follow-up is necessary to reconfirm them. This so-called “advancing a performance” becomes the guide for the person responsible for managing its success.

Among the other things the artist manager or tour manager does is meet with the promoter, or the person who hired the artist for the performance, during the show or immediately afterward to receive payment on behalf of the artist. Also at this meeting is a representative of the venue, who will receive an agreed-to percentage of on-site merchandise sales which we discuss later in this chapter. This is called the settlement meeting. If the performance did not require a promoter, the payment terms are as they were specified in the contract, which is usually cash, wire transfer, or certified check. If a promoter hired the artist, the manager or tour manager must compare the approved budget for the performance with the actual expenses and count the tickets sold for the event. The manager and promoter together total up the amount of money from the sale of tickets. Deducted from that total is either the approved promotional budget or the actual promotional budget, whichever is the lesser amount. The result is the profit from the performance.

Unless a performance is in a small venue and is being used for developing stage presence or seasoning the artist as a performer, an artist’s performance or tour appearances require very active promotion. This is achieved through publicity, advertising, and a presence on the web, especially through social networks. However, it depends on the career status of the artist whether all of these promotional avenues will be available.

A new artist without a contract with a record company will not be able to afford much advertising to support a tour. Artists in this category and small independent labels have very limited financial resources, so there is heavy reliance on publicity and social networking to promote an artist’s performance and to have it covered by local media when the show dates arrive. The artist manager works closely with the artist’s publicist to maximize potential local radio, television, and newspaper publicity. The manager of digital media for the artist must keep the artist’s website current and social networking sites buzzing with the most recent tour schedule, links to the venues, information about tickets or admission charges, and should be sending occasional emails, Twitter feeds, and Facebook postings to the artist’s contact list about additions to the tour schedule.

An artist who has an established fan base and who has had several recordings released in the past will find it easier to get publicity to support a performance or a tour. Simply releasing a recording on an independent label will give the media something to write about and generate new interest in the artist. The new recording, coupled with a tour and a unique story angle, can create a series of stories for the traditional media and provide ways to ignite the fan base through the use of social media.

For the artist signed to a larger label, the promotional efforts that will directly affect the sale of tickets include radio airplay, video plays on cable television, and video views on websites, especially in markets where the artist plans a tour stop. Labels will also assign a publicist to advance the scheduled performances. To the label, this kind of promotion helps them sell recordings while immensely helping the sale of performance tickets.

As the artist becomes well known and builds a sizable fan base, the artist’s booking agent will seek concert promoters who are willing to hire the artist for a performance in a particular market or for a series of performances on tour. The promoter is an entrepreneur. He or she pays all of the costs of producing and marketing a live performance, and as a result also takes all of the financial risk.

To minimize their risk, promoters purchase insurance on shows they produce. If an artist becomes ill and cannot make a committed performance date, the promoter will lose the money invested in promoting that date and must refund money to ticket holders. All of this can create an insurable loss to the promoter. An example is the exposure concert promoter AEG Live had with the untimely death of Michael Jackson just before his London concerts were to begin in 2009. The company had given Jackson a $10 million advance to agree to the performances, and paid another $30 million to produce the show for its theater performances. The insurance policy AEG purchased included a physical of the pop star, which showed him to be in good health, and it was intended to cover potential losses in the event the shows were cancelled. Without an insurance policy, AEG would have no way to recoup its losses from selling tickets and producing a show that never materialized. It was anticipated that the Jackson estate would return the advance but it is unknown whether the insurance policy was large enough to cover all of AEG’s losses (Mayerowitz et al. 2009).

For each performance, the promoter creates a budget, leases the venue, contracts with performers, hires local labor, leases all necessary production equipment and expertise, purchases all permits, pays all taxes and fees, pays for all marketing expenses, pays a performance license to the PRO, and supervises all aspects of the event. The specifics of all of these activities have the prior approval of the artist manager, and the tour manager has the final say on behalf of the manager on the day of the show.

When the show is over, the artist is paid the guarantee for the performance and the promoter is paid, for example, 15% of the net proceeds. This then becomes what is called the split point, which is the remainder of earnings from the performance. It is the amount at which the promoter and artist have agreed that they will begin sharing; at, for example, a ratio of 30% to the promoter and 70% to the artist. Agreements with promoters also include a net earning amount termed overage, which is the amount at which the artist takes all of the remaining excess earnings. It is easy to see that established acts require fewer services from a promoter because of the public awareness of the artist as a brand, but the inclusion of some sharing of excess earnings will help ensure that the promoter will meet the attendance expectations of the artist and the manager. However, the inclusion of a generous split point and overage with a new artist adds important incentives to the promoter. And there are circumstances in which an artist prefers to accept only a guarantee for their services, which may occur when the artist is dealing with an unfamiliar promoter or with one who has a history of high expenses. The terms most often used in budget preparation have different meanings for the potential earnings of an artist in a performance contract. They include:

• Gross potential—this is the total amount of all ticket sales if the concert sells out.

• Gross at settlement—this is the total the box office actually took in for all sales for the event before any expenses have been taken out of the total.

• Net—this is the value of all tickets sold for the event after fees and taxes have been deducted.

• Net net—this is the amount of taxes and agreed expenses that are deducted from the total proceeds from the box office.

(Barnet 2014)

When an artist manager considers contracting with a promoter, some care must be taken and the manager should look to the agent for advice if he or she has never used the promoter before. Some of the things the manager and agent should consider include the following:

• Does the promoter have a good overall reputation?

• How long has the promoter been in business?

• What is the promoter’s general success record, especially with this kind of an artist?

• Is the promoter strong in markets where the manager is planning performances for the artist?

• Can the promoter handle a complete tour?

• Does the promoter have good relationships with concert production service companies?

• Does the promoter have the financial resources necessary?

• Will a record label be part of the decision regarding the promoter?

Even for promoters with whom the manager has had some experience, occasionally revisiting some of these questions about them can prevent surprises that will have unpleasant consequences.

When the “promoter” is a casino, it means the casino pays a flat fee, and is offering free performance tickets to their frequent patrons and market—often aggressively—advance tickets sales to the general public. Complimentary tickets offered to gamblers that haven’t been picked up two hours before the show are offered for sale to gamblers in the casino or generally to the public. Events like these are convenient to fill open concert dates because there is a guaranteed payment for the performance regardless of the attendance, without a concern about ticket sales. However, it’s important that an artist who hasn’t performed in an environment like this understands how different this audience can be from a typical hard ticket concert event. Those who receive free tickets (soft tickets) may or may not care much about the artist but show up because they got something for free. Those who do attend the show might be noisy, rowdy, and rude, frequently leaving their seats to make nearby bar purchases. It can have a very different “feel” from a hard ticket concert, and the manager should prepare the artist for the kind of audience behavior they might face when they take the stage.

Live performance agreements contain basic information such as the name of the company or person hiring the artist, the date and time of the engagement, the specific location of the performance, the time and length of the performance, the services the artist will provide, and any riders to the contract. A rider is an attachment to the main portion of the contract that specifies standard production requirements for the artist’s performance, as well as any personal needs the artist has prior to and during the performance. Riders include very technical specifications for production crews to follow when preparing the stage for the performance. Riders can also include things such as a limousine service for the artist, elaborate food before the performance, expensive beverages, and luxurious dressing room accommodation. For major artists on tour, concessions of this type are often justified as a way to reduce the rigors of being on the road for lengthy periods of time. The new artist can expect small but reasonable personal concessions in a rider. However, all expenses associated with any rider are charged directly back to the artist as costs of the artist’s performance, and are deducted as an expense from the receipts from ticket sales. This is an important consideration for the artist manager or business manager as they create a budget for a performance or tour.

The performance contract or agreement includes the circumstances under which an engagement may be cancelled. Those reasons include the death of key personnel such as a band member, the tour manager, or production staff, and the health of the artist. If there is the possibility that the artist will be exposed to personal danger—for example, because of threats—the performance may be cancelled. Under all of these circumstances, the artist manager must return any deposits that have been paid. For the promoter, individual, or company hiring the artist, however, there generally is no recovery of their losses resulting from the causes for cancellation provided for in the contract unless they have purchased insurance to cover the potential losses.

The artist manager should include provisions in the contract that give him or her the right to approve advertising for the engagement and proof that the advertising was actually bought. The manager will also want approval of the distribution of all complimentary and promotional tickets to ensure, for example, that all radio stations in the artist’s musical format in the market are treated equally. As the manager reviews the list of people requesting premium complimentary seating, they should know that artists can become upset when people in the first two rows of a concert audience are people who are “suits,” or people who were given priority seating but aren’t the energized fans the artist would prefer to see in the front rows. A good rule of thumb is to make it a policy that priority seating for required complimentary tickets begins behind row five.

If the artist is the headliner for the performance, the manager should include language in the agreement that gives the artist and the manager the approval for any other artists who may appear on stage as opening acts. Other sections of the contract are specific about details of the performance, how licenses and permits will be handled, and how settlement and payment will be handled.

Selling artist’s merchandise at performances and on the artist’s website is another way live performances can quickly begin generating income to support the artist’s career. If the decision is made to offer merchandise for sale at performances, the artist and the manager must make an early commitment to purchase only the highest quality items they can afford for sale. Cheap merchandise makes a statement about the artist, so it is better to offer nothing for sale rather than something that is of poor quality.

It is the manager who arranges the production, manufacture, and sales of merchandise. However, as a new manager will quickly learn, this income stream can become extremely time-consuming. Among the steps in handling merchandise for the artist are:

• Creating a budget for merchandise

• Designing each item of proposed merchandise inventory

• Determining quality

• Determining quantity

• Ordering finished art

• Determining pricing

• Estimating obsolescence

• Getting bids from manufacturers

• Arranging manufacture

• Arranging shipment from manufacturer

• Arranging storage

• Purchasing insurance

• Creating and maintaining an inventory

• Determining when new designs of merchandise should be introduced for frequent market stops

• Packing and shipping merchandise to the location of each performance

• Paying hall fees to the venue to be able to sell the merchandise

• Arranging space and people to sell the merchandise at performances

• Arranging management of the sale of merchandise at performances; accounting, inventory, cash management, reports

• Packing remaining merchandise after the performance and shipping it back to storage

One budget item the manager should be prepared to see is something called hall fees, sometimes also called house rate (Barnet et al. 2007). Many arenas and other venues charge the artist 20–25% of merchandise income from a concert appearance as a fee for the privilege to sell merchandise at a venue (Palmer 2014). As is often the case, major artists have more negotiating power to be able to reduce those hall fees for merchandise sales because the venue will still be able to sell a large number of $8 slices of pizza, $6 soft drinks, and $10 parking fees.

Because of the time merchandise management can consume, managers often see the value of licensing the image and marks of the artist to a reputable merchandise company and making it their responsibility to create and sell merchandise at the artist’s performances. Merchandise companies pay onsite costs as well as licensing royalties to the artist ranging between 30% and 40% of the gross receipts, meaning that a $25 T-shirt will generate over $8 to the artist for each one sold.

Bootleggers are rogue merchandise sellers who appear near venues the day or evening of a performance and offer counterfeit merchandise for bargain prices. Because an artist has the right to their image in commerce through trademarking or service marking, the manager is responsible for alerting local authorities that people are selling illegal merchandise and press to have them arrested. This has been a problem that is difficult to police; however, many managers, promoters, and venue operators have had increasing success in stopping counterfeit sales with the assistance of local authorities.

Negotiating licensing contracts with merchandise companies can become somewhat complex; this is another area where the artist manager should be especially careful. The merchandise company will be expected to pay a royalty advance to the artist, and will want guarantees in the licensing contract of the minimum audience sizes at upcoming performances. The merchandise company is interested only in the number of people who actually pay to be part of the audience, feeling that those who receive free tickets are not closely enough connected to the artist to want to buy merchandise. If the audience estimates are too high, the contract will require the repayment of money advanced to the artist, and the artist may lose all of the benefits of licensing to the company.

The manager may also want the merchandise company to provide fulfillment of orders made from the artist’s website. Fans who click on merchandise on the artist’s site will be redirected to an order form at the merchandise company. Here, the company collects the payment, packs, and ships the merchandise to the buyer. The merchandise company provides these services to the artist for a fee, but for the manager who is not prepared to offer fulfillment services this can be a real time saver. If merchandise is handled in this manner, it is important that the artist’s webmaster maintain high-quality and current images of the items being offered for sale. These points are key determinants of the appeal of the merchandise to visitors to the artist’s site.

When preparing to offer a merchandise licensing agreement to a company, it is always advisable to seek the advice of an entertainment attorney who is experienced in this specialized kind of agreement.

Merchandise can be a large portion of a major touring act like KISS. Over the last fifteen years, KISS has sold a half billion dollars of merchandise of items ranging from coffins, to comics, to condoms. Their inventory of merchandise items they sell includes 3,000 items. For a Los Angeles tour stop it’s not uncommon for them to sell US$180,000 worth of T-shirts. (KISS 2011) While this stands as a high end in a a discussion about merchandise, for the self-managed artist early in career development the sale of music and merchandise at performances helps cover the costs of travel and other expenses of living on the road during those lean years.

A final note about live performance is to make the artist manager aware of Pollstar magazine as a planning and information resource. Pollstar is the trade magazine of the concert and touring industry that supplies weekly information about artists, venues, promoters, audience sizes, ticket sales, and gross earnings of live performances for hundreds of acts. It can help the artist manager with budget estimates, the timing of a tour, and will help identify agents and promoters who are successful with artists similar to the manager’s clients. The free online version of Pollstar gives information that is more useful to fans than to management. The actual magazine and the online subscription service offer the depth of information a manager will need.

Plans for international touring are often created to build a following in other countries before launching a career domestically, or planned at the end of a tour supporting an album that has nearly reached the end of its prime life cycle. One of the most famous groups that used international tours to launch a career in the United States is the Backstreet Boys. Manager Lou Pearlman put the group on international tours from 1994 to 1997, preparing them for the eventual acceptance by the fans of pop music in the United States (VH1 2005). Successful international touring for established artists almost always requires a successful album release at home, and labels will be reluctant to support an extended international tour until the domestic market has been served.

Touring in other countries has become more challenging after the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York, even after all of these years. Required paperwork can now include a letter of invitation from the promoter in order to get a passport, a visa (with a minimum of two blank pages), a work permit (in Canada), an international driver’s license, copies of signed contracts, a bond to assure customs officials that the artist will not sell any of their equipment while in the country, certification that travelers are healthy and have the necessary immunizations, a detailed equipment manifest, insurance policies, and a carnet.

A carnet is essentially a passport for the equipment being transported to another country for use by artists in their performances, and its use can expedite getting the equipment through customs in 75 countries. It also prevents tours from being required to pay import duties or taxes on equipment used for performances that will be leaving the country with the artist (Barnet 2006).

Managers of artists who travel internationally for touring or for pleasure must have a passport. It is the primary document required to permit individuals to enter into other countries, and to return to their home country. In January 2007, the United States began to require all international air travelers to have a passport when landing—even when traveling from border-friendly countries like Canada. However, a passport card, which takes less time to apply for and to receive, is intended for visitors to countries that border the United States but who are not flying. The manager should plan ahead by at least six weeks from the time a passport is needed for the artist and touring personnel to travel to its delivery, although the U.S. Department of State offers expedited passport processing that can be completed in two to three weeks (Department of State 2010). A word of caution to managers: some states in the U.S. will hold on to a passport of a member of the tour that has outstanding child support payments.

In this time of using online services to schedule travel, the services of a travel agent can be helpful when planning a tour. Some of the larger agencies that serve the music industry are aware of travel requirements to many destinations, and can be extremely helpful with occasional and onerous changes in itineraries. Other useful sources of information include the websites of embassies, the offices of the American Federation of Musicians, AAA, and online services from the U.S. Department of State.

American tour promoters who have international stops usually associate with promoters from the country into which the tour will go. Likewise, an artist’s agent in the United States will likely have agents who handle international bookings for them, and they often have offices in the United Kingdom that assist in coordinating international tour stops (Barnet 2006).

A final word of caution to the manager when planning international performances: be aware of the income tax regulations in the countries visited. For example, a series of tour stops in Canada requires that the company or individual who pays for the artist’s services withhold 15% of the gross earnings for each performance (Canada Revenue Agency 2010). Likewise, international artists will be required to pay income tax for earnings in the United States, with the largest international tours having an agent of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service assigned to track the earnings of the tour. In the U.S., the international artist is required to have 30% of their gross earnings withheld until they file their US income tax return. They can avoid the tax on gross earnings by filing an agreement that estimates their net earnings (earnings after touring expenses) (Dhar 2008).

College touring can be valuable for a manager who is helping an artist with building a fan base composed of this target market. Often engagements barely pay for the costs of the appearance but can add valuable experience for newer artists who are trying to learn about themselves in a live performance environment, and they can help build fan bases. Tour stops like these are typically soft-tickets, and are referred to by booking agents as “over-pay” for talent.

Managers will quickly find that most campuses have committees that have a fixed budget for the school year and plan appearances by artists based on available funds. It also means that there is a group of people making the booking decision rather than a single promoter or agent. Like most business that is conducted by committee, it is not quite as prompt as when there is one decision maker, so the manager should provide additional planning time, knowing that contract offers will be slower to arrive. Also, “the two organizations that college concert committees use to facilitate co-op buying—more than one school booking the same act when the schools are close enough to create good, short routing for the act” can benefit both the universities and the artist (Barnet 2014).

Some colleges use what is called a middle agent, whose job is to negotiate with managers or agents on behalf of the college committee. These agents work for the college, and can be helpful to managers who do not want to deal directly with the college (Ostrowski 2005). Other useful information for the artist manager considering a college tour is available through the National Association for Campus Activities. The organization conducts regional and national meetings and seminars that include opportunities for artists to showcase for college campus activity committees and middle agents.

Throughout this section of the book there are numerous references to Dr. Richard Barnet. Dr. Barnet is a colleague and has written the leading book on the subject of concerts and touring; you’ll find my reference to it below. I offer my sincere thanks to him for his contributions to this chapter.

I also offer my sincere thanks to former Warner Bros executive and veteran artist manager, Professor Christopher Palmer, for his contributions to this chapter.

References

Barnet, Richard. Personal interview. 2006.

Barnet, Richard. “Suggestions.” Message to the author. 6 Jan. 2014.

Barnet, Richard, Ray D. Waddell and Jack Berry. This Business of Concert Promotion and Touring. New York: Billboard Books, 2007.

Canada Revenue Agency. “Businesses—International and non-resident taxes.” Available online at www.cra-arc.gc.ca/tx/nnrsdnts/bsnss/menu-eng.html (accessed 21 Feb. 2014).

Dhar, Aninda. “Foreign Music Acts and United States Taxation.” Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 26 (2008): 151.

Dungan, Mike. Personal interview. 2007.

Kiss. “Kiss, Inc.” CNN Presents. CNN, 19 Oct. 2011.

Mayerowitz, Scott., Nathalie. Tadena, and Alice. Gonstyn. “Jackson’s Death Means Multimillion-Dollar Woes for Concert Promoter.” ABC News, 26 June 2009.

Ostrowski, Dan. “Booking College Shows.” Starpolish, 2008. Available online at http://65.61.2.9/advice/article.asp?id=24&original=1 (accessed 21 Feb. 2014).

Palmer, Christopher. Personal interview. Mar. 2014.

Passman, Donald. All You Need to Know About the Music Business, 5th ed. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

Pollstar. Available online at www.pollstar.com.

Vasey, John. Concert Tour Production Management. Burlington, MA: Focal Press, 1998.

VH1. “Backstreet Boys.” Behind the Music, 13 June 2005.