4.

ACTIVE INERTIA

A year into the recession, demand for vehicles continued to fall, major manufacturers went bust, and a sense of despair spread throughout Detroit. For Harvey Firestone, 1896 was turning out to be a very hard year.1 Firestone sold horse-drawn carriages in the Detroit branch of the Columbus Buggy Company, which produced high-priced vehicles until the recession forced the firm into receivership and Firestone out of a job. Firestone worked his network of personal contacts to identify another opportunity, and one afternoon he took an acquaintance for a ride in his carriage to discuss possible start-ups. His passenger commented on the smooth ride, which Harvey attributed to the buggy’s solid rubber wheels, the only set in Detroit at the time.

After a few hours of discussion, they concluded that rubber tires represented a marked improvement over wooden wheels rimmed by steel, the standard at the time. Firestone’s companion recalled a recently closed shop in Chicago that had specialized in pneumatic rubber tires for bicycles. That same night, the two men boarded a train to Chicago, and within a week they had purchased the bankrupt company’s equipment and supplies and began fixing rubber tires to buggy wheels. They focused their sales efforts on delivery firms and undertakers, who made frequent journeys with heavy loads. When the economy picked up in 1897, the rubber tire business boomed. The newly inaugurated president, William McKinley, spurred demand when he installed rubber tires on the carriages he brought to the White House.

Although the business boomed, Firestone was forced out of the company by his partners. Firestone, now thirty-one years old, was determined to sell rubber tires, and decided to relocate to Akron, known as America’s rubber capital, to start another tire firm. When Firestone arrived, eight existing rubber factories employed one-quarter of Akron’s labor force, and the city was known for the tang of molten rubber that hung in the air, and snow blackened by factory smoke. Akron was a boomtown, growing faster than any other city in the United States between 1910 and 1920. The number of residents at times exceeded available beds, forcing tire workers to sleep in shifts.2 Firestone worked for a few months selling rubber-cushioned horseshoes and solid rubber tires before splitting off to found his own company in 1900.

The rubber tire industry ranked among the world’s most turbulent. Tire demand followed the explosive growth in automobile sales. In the first decade of the new century, horseless carriages moved from an expensive hobby to an affordable consumer good after Henry Ford offered the Model T for sale in 1908. In the first twenty-five years of the century, automobile sales grew a thousandfold, increasing tire shipments from a few thousand in 1900 to nearly sixty million twenty-five years later. More than two thousand new companies entered the automobile industry, experimenting with a wide range of power sources (including steam, gasoline, and electricity), designs, and manufacturing processes. The diversity generated widespread uncertainty about which product designs, manufacturing processes, and strategies would ultimately succeed.3

Diversity among tire companies mirrored that of automakers. More than five hundred entrepreneurs entered the tire industry, lured by the promise of fame and fortune. The most successful founders, including B. F. Goodrich and Harvey Firestone, became household names, and Akron’s tire industry had produced more than a hundred millionaires by 1920. Like the automakers, these companies experimented with a wide range of technologies.4 In the span of twenty years, the industry passed through three dominant designs for the tires themselves, and two distinct ways to attach them to rims. These product innovations ultimately improved the life span of a tire from five hundred miles in 1900 to twenty thousand miles thirty years later. In the first three decades of the nascent industry, rubber executives contended with technological tumult, patent disputes, the formation and dissolution of industrial trusts, fluctuations in raw material prices (especially for rubber), volatile interest rates, a world war, labor unrest, recessions, and the Great Depression.5

Bust followed boom. Overcapacity led to vicious price wars throughout the 1920s and 1930s, when the average price of a tire fell by 80 percent.6 Competition resembled a limbo contest, with the tire companies bending over backward to cut costs below a price bar that kept slipping lower. The most efficient firms maintained profitability by increasing productivity, including a fivefold increase in the number of tires produced per manufacturing employee.7 The laggards exited the industry. By 1937, the total number of tire manufacturers had dropped to just over fifty, and the five largest controlled in excess of 80 percent of the domestic tire market. Four of the five leading firms had their headquarters in Akron. Firestone Tire & Rubber survived the shakeout and emerged as the third-largest tire maker in the United States, ranking among the sixty largest American enterprises.

INESCAPABLE COMMITMENTS

The map paradox arises whenever people must make long-term commitments based on an imperfect mental map. In the last chapter we saw that the provisional nature of future knowledge renders all maps imperfect, and in this chapter I will argue that commitments are nevertheless unavoidable. A commitment, as I use the word throughout this chapter, refers to any action people take in the present that binds them (or their organization) to a future course of action.8 Common commitments include official declarations such as President George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq, signing a contract, investing in specialized resources such as a tire factory, or deepening a relationship.

People crave certainty about the future before making long-term commitments. A newlywed couple shopping for their first house would like to know future real estate prices, interest rates, and their own incomes before taking on a mortgage. Turbulence, however, clouds visibility into the future and can sap the confidence to commit. In 1910, Harvey Firestone had to decide whether to invest the company’s available cash in rubber for the next year’s production, without a clue about future demand, prices, or raw material costs. “I have never known a time when I was so undecided,” Firestone fretted. “It places you in a position where you are afraid to buy and afraid not to buy.”9 Investors who considered equities in 2009 would recognize Firestone’s predicament.

In Firestone’s position, many executives might be tempted to avoid commitments altogether to keep their options open and avoid making a mistake. Others might resort to tentative commitments to hedge their bets—recall how Royal Caribbean executives sliced their ships in half to extend capacity rather than commission a new ship, as Carnival did. The absence of certainty, however, does not eliminate the need to commit. Even in the most turbulent contexts—a nascent industry, war, or geopolitics—people must make commitments that are consequential and difficult to reverse, for the reasons outlined below.

Commitments can convince others to provide necessary resources. Scientists need government grants to fund research, presidents needs allies’ support to fight wars, and entrepreneurs require cash, labor, and technology to build a company. Lacking certainty about the future, the resource owners may dither, reluctant to invest in a risky undertaking. A bold commitment can induce them to commit. Henry Ford hesitated to give Firestone a large share of his business, fearing the start-up could not keep pace with Ford’s growing demand for tires. In 1910, Firestone decided to build a new factory, among the largest in the world at the time, to assure Ford that his company could meet the automaker’s needs. Firestone agonized over the decision but in the end concluded the massive plant was the only way to convince Ford to give him the business. Skilled rubber workers, to give another example, had their choice of employers in Akron’s overheated labor market. To attract and retain crucial workers, Harvey built Firestone Park, a community with hundreds of houses that workers could purchase at below-market rates provided they stayed with the company.

Commitments also maintain focus on critical concerns amidst the myriad distractions that arise in churning markets. The corporate name Firestone Tire & Rubber committed the company to a strategy of supplying tires to the booming automobile market. Other early entrants lacked Firestone’s clear focus. Some defined themselves as rubber companies, selling rubber products ranging from rain boots to conveyer belts. Serving a hodgepodge of markets distracted them from the booming automobile market. Other entrants produced myriad automotive components and failed to stay on the frontier of rubber chemistry.

People must also commit to building specialized resources to sustain a competitive advantage against competitors. In business, firms create and sustain value to the extent that they control tangible or intangible resources.10 To create value, a resource must have three characteristics: First, it must create economic value by cutting costs (think Wal-Mart’s logistics) or increasing customers’ willingness to pay (think of shelling out $5 for a latte at Starbucks). Second, a resource must be rare—if every car included BMW’s technology, the German automaker could command no premium. Finally, it must be difficult for competitors to substitute an alternative resource—Saudi Aramco’s oil stockpiles will remain valuable until cars can run on alternative fuels. Valuable, rare, and inimitable resources create sustainable competitive advantage outside business. Superior military technology aids the U.S. armed forces, while LeBron James carries the Cavaliers to the playoffs.

Harvey Firestone invested heavily to create valuable, rare, and inimitable resources. In addition to the state-of-the-art plant, he spent lavishly on advertising—Firestone sponsored the winner of the inaugural Indianapolis 500—to build a brand associated with quality and value. He also built expertise in rubber chemistry, tire design, and manufacturing processes. In an era when few U.S. firms had dedicated research departments, Firestone hired the company’s first research chemist in 1908 to build a laboratory. In subsequent decades, the company’s engineers and scientists produced a steady series of incremental innovations that cumulatively improved product safety, quality, and durability while chipping away at costs. The gains did not come through any single breakthrough. Rather, the research trajectory doled out its benefits over time.11

In terms of building expertise, Harvey Firestone’s most important commitment was his initial move to Akron. As the tire industry grew, an ecosystem of supporting institutions cropped up in America’s rubber capital, including a college that offered the nation’s first rubber chemistry course, technical testing firms, and the leading industry trade journal. The Portage Country Club, founded by two B. F. Goodrich executives, provided the social setting where the founders, managers, researchers, and investors in tire companies congregated to socialize and talk shop.12 By committing to Akron, Firestone ensured that he and his employees remained in the flow of technical and business information, which helped them stay on the cutting edge of rubber technology. Akron firms accounted for more than 80 percent of the major improvements in tire and rim design and nearly two-thirds of innovation in raw materials and tire components through the early 1930s.13

Commitments can yield efficiency as well as expertise. Firestone’s bold capacity expansion conferred economies of scale, which he passed on to customers through price reductions while still pocketing some additional profit. Firestone committed to standardized manufacturing processes to maximize efficiency. Before building their new plant, Firestone and his engineers built a tabletop mock-up of the factory and spent hours pulling string through the model factory to simulate alternative flows of materials. By tailoring the plant to a specific manufacturing process, Firestone gained efficiency but limited the company’s ability to modify its work flow in the future,

Commitments also fortify confidence. Commitments attract others, focus effort, build sustainable competitive advantage, and increase efficiency. Taken together, these benefits increase the odds of success, and thereby bolster the confidence to make future commitments. Firestone agonized before building his new plant, but once built, the factory reduced costs and secured a large share of Ford’s business, emboldening Firestone to make bigger bets in the future. The virtuous circle linking confidence to commitment, and commitment to success feeds upon itself. Success also reassures outsiders. As long as Firestone continued to make bets and win, Ford renewed its orders, bankers made loans, and workers remained loyal. Commitment and confidence are the critical links in a chain that drives progress.

Repeated cycles of commitment and success build momentum. In his first two decades, Firestone was sued three times for patent infringement, was excluded from a cartel, and faced a recession so bad that creditors unseated management at his two largest competitors. Early failures need not spell ultimate defeat, however, and Firestone made a series of commitments that maintained momentum to overcome these setbacks. After founding his eponymous company, it took Firestone a decade to build the first plant, two decades to perfect the tire, and three decades to emerge as a clear winner. Commitments built the momentum to stay the course.

Commitments do not, of course, guarantee success. Not all investments work out. Recall how Internet start-ups like Flooz.com and Boo.com invested heavily to build brands that never increased customers’ willingness to pay. Even if a commitment yields anticipated gains, unforeseen shifts in the external context may cause failure. Firestone could have built his plant, secured the economies of scale, and still gone bankrupt if a recession decreased demand or Ford stumbled. Commitments are necessary but not sufficient for success in a turbulent world.

REINFORCING COMMITMENTS

People often equate commitments with major life choices, such as getting married or choosing a profession, where they make explicit vows after considering consequences and alternatives. Many important commitments, however, look nothing like these once-in-a-lifetime vows. Instead, people stumble into commitments without noticing, let alone evaluating them. The scope of these commitments is not spelled out at the outset but takes shape gradually over time and crystallizes long after the initial steps are taken. A single big bet rarely determines the future. Instead, a densely interwoven tangle of commitments, varying in size and form, initially define the details of a mental map, and then reinforce them.

Most mental maps begin as little more than a hunch. When Firestone committed to sell rubber tires, his plan resembled a nearly blank treasure map: X marked the opportunity, but the chart was otherwise devoid of signposts indicating how to get there. Firestone began pursuing the rubber tire opportunity long before he knew exactly what his commitment entailed in terms of marketing, technology, manufacturing, or customers. People rarely fill the blank space of their mental map through systematic long-term planning. Instead, they respond to immediate opportunities and threats as best they can. When the tire rim cartel excluded Firestone, he innovated around their patent and embarked on an uncharted technological trajectory. He built a plant to secure Ford’s business and subsidized housing to retain workers. There was no grand design, but instead a series of workable solutions to unforeseen challenges and opportunities. These ad hoc commitments accumulated over time, filled out Firestone’s map with greater granularity, and defined the character of an enterprise. A similar dynamic occurs in any new undertaking—whether a new company, scientific community, or presidential agenda.

Commitments do not cease once the details of a map have stabilized. Subsequent commitments, however, reinforce the emerging status quo rather than define it. Reinforcing commitments are actions that buttress an elaborated map, and they come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from bet-the-company investments implicit in a new plant to small steps such as incremental tire innovations. Despite differences in scale, reinforcing commitments build on the past. They resemble the ruts cut by the wheels of carts passing along a dirt path. The established grooves channel the cart’s path, and each passing vehicle deepens the rut.

Reinforcing commitments confer important benefits: they focus attention and concentrate effort on what really matters; they attract employees, customers, and partners who fit well with what the company stands for; they decrease costs (maintaining a current customer, for instance, tends to be much cheaper than landing a new one); they help manage risk (refining an established technology is safer than pioneering a new direction). When extant reinforcing commitments are costly to replicate, they prevent competitors from easily securing the same benefits. Whether baby steps or big leaps, reinforcing commitments enhance speed and reliability along established routes—you can’t drive 60 mph on a cart path. Five types of commitments—to frames, resources, processes, relationships, and values—reinforce mental maps with particular force.

Frames focus attention within a narrow segment of a mental map. For companies, the choice of geographic scope, for example, demarcates opportunities they consider from those they ignore. U.S. Steel executives defined their market as North America, thereby discounting opportunities that Mittal considered. Specific metrics to measure success are another important frame. Firestone tracked its share of tires sold to Detroit automakers to a tenth of a percent, celebrating any gain at the expense of competitors. Choice of competitors that matter most—Akron tire makers or Miami-based cruise lines—is another important frame that focuses attention.

FIGURE 4.1 Reinforcing Commitments

Resources include both hard assets, such as steel factories, and intangible assets, such as Carnival’s brand or Firestone’s technology. The best resources are not only valuable, rare, and inimitable; they are also aligned with a specific mental map. To ensure distribution in the face of heated competition from Sears Roebuck and other retailers, Firestone increased the number of company-owned retail stores from 9 to 430 in the span of four years. After Harvey died in 1938, his sons, who ran the company for the following four decades, continued to invest in resources to support their father’s map. The company integrated backward into a million-acre rubber plantation in Liberia to ensure a secure flow of raw materials at predictable prices.

Processes are the recurrent procedures used to get work done. They include operating procedures, such as logistics or production, and managerial ones, such as decision making and resource allocation. Standardized processes increase efficiency, enable firms to scale, and facilitate coordination among different units. In the 1920s, Firestone’s technical team invented “gum-dipping,” a manufacturing process that soaked strips of cloth in rubber and then cured them so they assumed a uniform shape. Gum dipping dramatically increased a tire’s durability, and the company spread the new process through all of its plants.

Relationships are the associations forged with external individuals and organizations—customers, regulators, suppliers, distributors, and other partners—who provide resources critical for success. Early relationships secure resources and confer credibility. If partners thrive, the relationships contribute to a firm’s success. Harvey Firestone befriended Henry Ford, and the ties that bound the two were knotted more tightly when Harvey Firestone’s granddaughter, Martha Firestone, married William Clay Ford, Henry’s grandson and the largest shareholder in Ford Motors. Sixty years after the Model T, Firestone was still Ford’s primary tire supplier, accounting for nearly one-half of Ford’s tires.

Values are the shared norms that unite and inspire employees. They are established through both statements and actions. The first people an entrepreneur hires, for example, can leave a lasting impression on a company’s culture. Strong values attract employees, fuel their passion, and build strong bonds of loyalty. Harvey Firestone committed to a set of corporate values to bind his company “as a family.” In an era of widespread labor strife, Firestone viewed his workers paternalistically. Not only did he draw on the corporate coffers to build subsidized housing, he also introduced an eight-hour workday for all employees and built the Firestone Country Club, open to all employees regardless of rank to provide a setting where employees from all levels could socialize.

FIGURE 4.2 Examples of Reinforcing Commitments

Frames

- Commit to share leadership in core market

- Declare traditional competitor public enemy #1

- Refine existing success metrics

Resources

- Focus R&D expenditure on refining core technology

- Invest in advertising to reinforce existing brand image

- Extend existing brand into closely related markets

- Build specialized facilities to support strategy

Processes

- Codify best practices in process manuals

- Replicate existing processes in new facilities

- Require suppliers to conform to your processes

Relationships

- Invest in technology or capacity to serve existing customers’ needs

- Require suppliers and partners to use your information systems

- Integrate backward into components or forward into distribution

- Tighten relationships with partners through joint venture or merger

Values

- Promote people who exemplify core values

- Banish renegades who challenge established culture

- Codify values and distribute to employees

Piling reinforcing commitments one atop another makes it harder to change the underlying map. Fred Smith had the idea for Federal Express while writing an undergraduate term paper about air freight shipping, and translated his map into reality through large investments in brand, trucks, planes, specialized information technology, and a freight handling hub. Rewriting a term paper is much easier than changing a global delivery network underpinned by difficult-to-reverse commitments. The dense interrelationships among established commitments further complicates the difficulty of unpicking one without disrupting others. Eliminating a single route or service for FedEx reverberates through the entire system.

The weight and interconnection among reinforcing commitments is not the only obstacle to modifying a map. Decision makers are also reluctant to admit—to themselves and others—that earlier commitments were wrong.14 This reluctance to reverse commitments, especially those made with much public fanfare, can lead people to escalate commitment to a flawed map even as evidence piles up that things are getting steadily worse.15 The United States’ escalation in Vietnam is a classic example of escalating commitment. Finally, when mental maps go unchallenged for extended periods of time, they slip into the background of taken-for-granted assumptions that people no longer consciously notice.16 Maps are most likely to become invisible when they have been held for a long time, have worked well at some point in the past, or are shared by many people.17

ACTIVE INERTIA

The hardening of commitments over time locks an organization into a map, which is fine as long as the environment continues to reward progress along the established trajectory. Problems arise, however, when shifts in the external context render the map outmoded or obsolete. After decades of relative stability, the tire industry faced renewed turbulence when French tire maker Michelin introduced the world’s first steel-belted radial. The new tire lasted twice as long as the old design, reduced blowouts, rode smoother, and increased fuel economy. Rolling on the strength of its new product, Michelin built twenty-six radial tire factories in Europe between 1960 and 1972, most outside France, and by the early 1970s Michelin led the European tire industry in market share. Michelin’s successful assault forced the European tire industry to restructure itself as struggling competitors merged and closed plants. Firestone watched Michelin pummel its rivals from ringside seats, since Firestone had competed in Europe since the 1920s.18

The action moved closer to Akron in the late 1960s, when Michelin began selling its radial tires through Sears, opened a $100 million radial tire plant in North America, and convinced Ford to include the Michelin radial as standard equipment on the 1971 Lincoln Continental. Shifting market conditions provided both an opportunity and a threat for Firestone. The company could steal a march by introducing and promoting its own version of the new technology in North America before its rivals. By waiting too long, however, Firestone risked the same fate that befell European tire manufacturers who failed to prevent Michelin’s aggressive drive to dominate the market.

Firestone neither seized the opportunity nor mitigated the threat. Instead, the company responded by doing more of what had worked in the past. Executives disparaged the “foreign” technology as unsuitable to American cars and inferior to products designed in Akron. Firestone produced an incremental improvement to its existing tire design that required only minor changes to its production process.19 This modified tire, known as the belted bias, gained initial market share until customers realized it offered no real benefits and switched to radials. In 1972, Ford announced its intention to place radials on all its models over the following few years, and General Motors made a similar announcement a few months later. Firestone managers responded to Ford’s request and approved investments to ramp up radial tire production and introduce the Firestone 500 Steel Belt brand radial tire. To speed the transition, the company manufactured the new tires using a slight variation on its existing production process.20 Firestone managers failed to close the existing plants rendered obsolete by their investment in the new technology.

Firestone fell prey to active inertia, the tendency of established organizations to respond to changes by accelerating activities that succeeded in the past. As turbulent markets throw out new opportunities and threats, organizations trapped in active inertia do more of what worked in the past—a little faster, perhaps, or tweaked at the margin, but the same old same old. With radials on the horizon, Firestone kicked its new product development process into overdrive, extending its established product. When that failed to stave off the radial, the company employed existing processes to make the new tire, and failed to close its redundant plants.

Organizations trapped in active inertia resemble a car with its back wheels stuck in a rut. Managers see market shifts, step on the gas, and race the engine in an increasingly frantic effort to pull themselves out of the rut. Instead of digging themselves out, however, they only dig themselves deeper. The ruts that channel their behavior are the very commitments—now numerous, hardened, and deeply intertwined—that underpinned their historical success. When stale commitments meet turbulent markets, the result is often active inertia. Figure 4.3 lists some common warning signs that commitments have hardened, putting an organization at risk for active inertia. Existing commitments lock firms into active inertia in several ways, described below.

Frames that once focused attention on what really mattered become blinders curtailing the peripheral vision required to spot unfamiliar opportunities and threats. In the late 1960s, the Firestone family still owned approximately one-quarter of the firm, and three of the founder’s five sons sat on the board. All of Firestone’s top managers had spent their entire career with the company, two-thirds were Akron born and bred, and one-third had followed in their parents’ footsteps as Firestone employees. Steeped in the company’s traditional map, the team dismissed competitors based outside Akron, remained confident in proven technology, and relied on their long-standing relationship with Ford to weather the storm.

Firestone was neither the first company nor the last to be caught in active inertia as its frames hardened into blinders. When Xerox executives surveyed the competitive market in the 1970s, they saw IBM and Kodak as the enemy, their forty thousand sales and service representatives as crack troops, and patented technology as an insurmountable barrier to entry. Xerox’s frames provided the focus to defend its position from repeated attempts by IBM and Kodak to attack its core market. These frames also blinded Xerox to opportunities arising from new technologies, and the threats posed by guerrilla warriors such as Canon and Ricoh, which sold high quality compact copiers to small firms, circumventing the sales force and technology that protected Xerox in large companies. When frames harden into blinders, executives, like generals, tend to fight the last war.

FIGURE 4.3: Warning Signals of Active Inertia

- Cover curse. Your CEO appears on the cover of a major business magazine. Of the first seven Forbes companies of the year, none subsequently outperformed the stock market, and three of the CEOs who graced the cover were fired. Praise from the press reinforces management’s attachment to their commitments and may breed hubris.

- Guru jinx. Management gurus single out your company as outstanding. The seminal management best seller In Search of Excellence identified a series of companies including Atari, Wang, and Data General, which subsequently stumbled. Public praise can reinforce management’s confidence in their existing commitments. No organization is immune to active inertia, and successful companies mentioned in this book, including Mittal and Carnival, will stumble unless they too adjust their commitments as circumstances change.

- CEO writes a book. Executives write a book articulating the secret of their success, and thereby link themselves publicly to past commitments. Backing away from a conspicuous and explicit statement of commitments is difficult. Publishing a book after retirement, as Jack Welch and Lou Gerstner did, is safe.

- Edifice complex. Building a grand corporate headquarters often signals that executives have declared victory and wish to commemorate their triumph. Executives who build grand monuments to their success are rarely in the frame of mind to question the commitments that got them there. The most dangerous buildings contain indoor waterfalls, feature heliports, or win architectural awards.

- Name a stadium. Rather than building new monuments, companies sometimes place their names on professional sports venues, including Compaq, Ericsson, Conseco, and Enron, not to mention PSINet, CMGI, Network Associates, and several airlines, including United, Continental, American, Air Canada, America West, and Emirates.

- Competitors share the same zip code. Entire communities of similar companies can fall prey to active inertia. Examples include Akron’s tire companies, automakers in Detroit, steel producers in Pittsburgh, minicomputer firms along Boston’s Route 128, Korean conglomerates headquartered in Seoul, and investment banks on Wall Street. Densely interwoven professional and personal networks tend to reinforce existing commitments and limit fresh information and new ideas.

- Top executives look like clones. A homogenous group of top executives often selects and promotes other executives based on their adherence to existing commitments. They also lack the diversity to envision alternatives.

Shifts in the market can devalue once valuable resources and leave them hanging like millstones around a firm’s neck. Firestone’s initial delay in building new radial plants was based in part on a rational desire to protect its existing asset base. The investment in radial production cut the total number of plants needed in half, because radials lasted twice as long as the tires they replaced. The new factories, moreover, required massive capital expenditures for uncertain returns. Transatlantic cruise lines faced the problem of “millstone” resources. When flights between Europe and America undercut their business, a few established lines tentatively explored Caribbean cruises. Their ships, however, were designed for a rough Atlantic crossing and therefore lacked the exposed deck space required for cruises in tropical climates. The strict separation into first, second, and “steerage” classes ran counter to the shared experience sought by Caribbean cruisers.

Well-oiled processes can lapse into mindless routines, which people follow because they are familiar, not because they are optimal. Firestone responded to unprecedented events with traditional processes. The company kicked their established product development process into overdrive to extend the existing tire design. When that didn’t stop radials, Firestone managers employed existing production routines to make the Firestone 500. McDonald’s is another case where long-established routines hindered a company from responding effectively to markets shifts. In the early 1990s, McDonald’s had a 750-page operating manual specifying every aspect of the business. For decades, corporate leaders standardized processes to ensure uniform results among franchisees. As consumer preferences shifted to healthier foods and new entrants heightened competition in the 1990s, McDonald’s was trapped by its old routines. The company’s single-minded focus on refining its mass-production processes stifled innovation that might have bubbled up if franchisees had enjoyed more leeway to experiment with alternative procedures.

Relationships become shackles that prevent a firm from adjusting to shifts in a turbulent market. Harvey Firestone’s personal friendship with Henry Ford lifted his tire company to industry leadership. But when circumstances shifted, that relationship hindered Firestone’s freedom to respond. Firestone depended on Ford for volume to keep its plants full and therefore felt compelled to produce radials when its largest customer demanded them, even though Ford refused to pay higher prices to help offset the required capital investment. Firestone executives maintained a cozy oligopoly with other Akron tire makers. Firestone executives often golfed in a foursome with their counterparts at General, B.F. Goodrich, and Goodyear, joking that Uniroyal could never relocate to Akron because it’s awkward to golf in a fivesome. Deep relationships with competitors hindered Firestone executives from breaking rank and marketing radials ahead of the other U.S. tire makers.

In the late 1990s, Compaq Computer was ensnared by its existing relationships. The company had risen to leadership in the personal computer industry through tight relationships with distributors, which resold Compaq’s PCs. Dell then began selling computers directly to consumers, first by telephone, and later over the Internet. Compaq executives recognized consumers’ growing preference to shop online and the cost advantages of Dell’s model. Moving to a direct model, however, would alienate the distribution partners responsible for Compaq’s rise to industry leadership, and still accounted for the vast majority of their sales and profits. The handshakes that once enabled success now acted as handcuffs hindering Compaq’s response.

Values ossify into stone-cold dogmas that channel behavior into existing ruts. Replacing the old tires with radials that lasted twice as long meant U.S. tire manufacturers would need to close obsolete factories. American tire makers ultimately closed twenty-nine of the fifty-seven domestic plants making bias tires in 1972. Although Firestone accounted for nearly one-quarter of domestic production, the firm closed far fewer than its share. Firestone’s cumulative pretax loss from delaying necessary plant closure exceeded $300 million, twice the magnitude of the Firestone 500 write-off.21 Top executives could not reconcile Firestone’s “family values” with layoffs. When addressing investors, Firestone’s CEO repeatedly referred to employees and communities as part of the “worldwide Firestone family” and requested shareholders’ patience while management tried to increase profits without harming employees or communities. Although “family values” are understandable and even admirable, dogmatic adherence to them can prevent executives from making difficult changes.

The British fashion house Laura Ashley provides another example of hardened dogmas. Laura Ashley founded the company that bore her name to protect the traditional British values that she saw as under siege during the 1960s. She created a series of frilly frocks that embodied the conservative values and modesty she held dear. These clothes, and the values they exemplified, appealed to a large number of women around the world—many bought Laura Ashley clothes, and a few signed up as franchisees. As more women entered the workforce, however, demand for Laura Ashley’s floral dresses dropped. The company struggled to adapt its hardened values to the new realities, and it now struggles on in a weakened form.

The costs of active inertia proved high for Firestone. By 1979, the company’s financial condition had grown acute, and it faced bankruptcy. More than seven hundred irate investors crowded into the company’s 1979 stockholders’ meeting, including one dissident investor who proposed firing top management, liquidating the company, and distributing the proceeds to owners. Within a year, the CEO retired at age fifty-seven for “personal reasons” and was replaced with an outsider, who saved the company from bankruptcy without restoring it to competitive health. Japanese tire maker Bridgestone subsequently bought Firestone.

When companies stumble in turbulent markets, their leaders are often accused of failing to see the changes coming. That is almost never the case, as the Firestone case illustrates. Michelin’s entry and the possible consequences were undeniable after the French tire maker routed its European rivals, opened an American plant, and sold radial tires through Sears. Firestone executives had ample evidence that their existing map no longer corresponded to changed market realities. A series of events surprised Firestone executives, including Ford’s decision to mount radials on the Lincoln Continental, Detroit’s abrupt switch, and failure of the belted bias tire to fend off the radial. These events showed up nowhere on their well-creased map, and indicated that something was amiss.

Firestone executives were also surprised by problems when the Firestone 500 tires experienced blowouts.22 In 1978, the company agreed to a voluntary recall of 8.7 million Firestone 500 tires at a cost of $150 million after taxes, the largest consumer recall in U.S. history.23 Firestone top executives also lost the ability to anticipate future earnings.

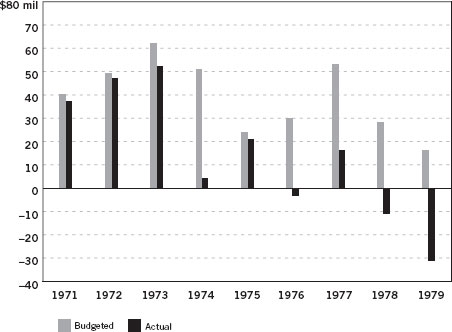

The gray bars in figure 4.4 plot the profits Firestone executives budget a year earlier, while the black bars note the actual profitability. In the first few years of the decade, the management team forecast profitability with better than 90 percent accuracy. In later years, the gaps between their forecasts and actual results widened. Their long-established map no longer provided a reliable guide to a more turbulent market.

Firestone’s decline was understandable but far from inevitable. Crosstown rival Goodyear was led through the 1970s by a CEO who spent his entire career with the company, but nearly all of it in international operations. Having lived through the European experience firsthand, he revised Goodyear’s map to incorporate radial technology. B. F. Goodrich brought in a CEO from outside the industry who quickly concluded that radials were bad for the tire business. B. F. Goodrich limited investments in the tire division, redeployed resources into more promising business units, and ultimately divested the tire division. The first step, in both of these cases, was management’s willingness to acknowledge that their map no longer represented the terrain and to explore the discrepancy in greater depth, the subject of the next chapter.

FIGURE 4.4 Firestone After-Tax Profit: Budgeted (Shaded) and Actual ($ Million), 1971–1979