11.

AGILE ABSORPTION

On October 30, 1974, George Foreman, the reigning heavyweight champion of the world, joined hands with his cornermen in his dressing room. The men bowed their heads in silent prayer.1 In a few minutes, Foreman would enter the ring to defend his heavyweight title against Muhammad Ali, in a bout dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle,” held in Kinshasa, Zaire, and broadcast around the world. The stakes were high for both fighters, who would split a $10 million purse, with the winner carrying away the championship belt. Foreman and his cornermen did not pray for victory, which they took for granted. Rather, they implored God to protect Ali from serious injury in the ring.

Today, the name George Foreman evokes late-night television advertisements in which an avuncular man clad in an apron pitches a low-fat grill. In his prime, the name George Foreman struck terror in his opponents. Foreman’s sheer bulk, physical strength, and toughness conferred absorption, or the ability to weather all the punishment his opponent could dish out. Foreman lacked agility, to be sure. In his prefight taunts, Ali compared Foreman to a mummy, shuffling with an awkward gait. Foreman compensated for his lack of bob-and-weave dexterity with his ability to weather blows, waiting for his adversary to tire or drop his guard. Then he unleashed the knockout blow. Foreman arrived in Kinshasa with a record unblemished by loss and stacked with forty wins, all but three by knockout. In the three years preceding the Rumble, Foreman won 90 percent of his fights by knockout or TKO before the end of the second round.

Foreman entered the Rumble a three-to-one favorite, and many thought the odds should have been longer. Foreman had dispatched fighters including Joe Frazier and Ken Norton, who had beaten Ali. Even Ali’s cornermen worried about their boxer’s safety. Ali’s doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, marveled at the way Foreman had knocked Frazier around like a child.2 Pacheco commissioned a jet to wait near the stadium, its engines running, with a flight plan to the nearest world-class neurological hospital. The young Ali epitomized agility, which enables a boxer to spot an opportunity—the hint of a sagging right arm or upturned chin—and exploit it before his opponent adjusts. Still, entering the Rumble, Ali’s agility seemed no match for Foreman’s capacity to absorb punishment.

The defining characteristic of the Rumble, or any boxing match, is uncertainty. Fighters can study tapes of past fights or select sparring partners who simulate an opponent’s style, but they cannot predict a blow-by-blow chronology of a fight in advance, foresee spikes in confidence, foretell the errant punch that splits an eyebrow, or anticipate a wily foe’s tactics. Competing in turbulent markets can feel a lot like entering the ring against George Foreman in his prime—or, even worse, like stumbling into a barroom brawl: The punches come from all directions, include a steady barrage of body blows and periodic haymakers, and are thrown by a rotating cast of characters who change the rules abruptly, swinging bottles and bar stools as well as fists.

The Rumble illustrates that agility, for all its benefits, is not the only, or even the best, way to master turbulence, in the ring and beyond. Absorption—the ability to withstand shifts in the competitive context—is a potent alternative. Agility and absorption are not mutually exclusive, and true champions combine them to achieve agile absorption—the capability to identify and seize opportunities while retaining the structural characteristics needed to weather changes.

ABSORPTION

Outside the ring, absorption results from structural factors that permit an organization to survive changes in its environment. Firms can build absorption in several ways, including obvious levers such as size, diversification, and a war chest of cash. Others factors, such as high customer switching costs, low fixed costs, and a powerful patron, can also buffer a firm against environmental changes, although in less evident ways.

Several factors enhance absorption, the most obvious being sheer size. Larger firms that control more resources and a greater market share can weather more storms for a longer time than smaller rivals.3 General Motors accounted for approximately one-half of all cars sold in the United States in the 1950s. The automaker’s large asset base and domestic market share allowed it to survive a steady erosion at the hands of more agile competitors, such as Honda and Toyota, in subsequent decades. Like a slowly sinking ship, General Motors has stayed afloat by steadily throwing ballast overboard—shuttering plants, discontinuing brands, and selling businesses. Initial size conferred the ballast to hold on for as long as General Motors has. At some point, a firm may become “too big to fail,” when sheer scale raises the cost of failure for governments, banks, customers, and unions, which have high incentives to intervene to prevent collapse. Diversification enhances absorption by allowing an organization with varied sources of cash flow to withstand hard times in one or more of its portfolio businesses. Absorption comes from diversification of cash flows, not revenues, and a collection of money-losing subsidiaries in a conglomerate can no more buttress one another than can a group of drunks staggering down the street, leaning on one another for support. A diversified portfolio also acts as a store of wealth that can be accessed to weather future storms. To subsidize its long decline, General Motors has sold off some of the jewels from its historical diversification, including Terex, Frigidaire, Raytheon, EDS, and Hughes, among others.

FIGURE 11.1 Bulking Up for the Fight

Source

Low fixed costs

Benefits from this source of absorption…

These can help a firm weather a wide range of changes, such as price wars, higher raw material costs, and declining demand.

…but beware

Leaders must maintain relentless pressure on costs, especially when times are good.

Source

War chest of cash

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Cash is perfectly fungible, so it can be deployed against future contingencies that managers cannot foresee.

…but beware

Executives must win owners’ confidence to stockpile the cash rather than paying it out to shareholders.

Source

Diversified cash flows

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Companies can withstand downturns in specific units, and diversified units serve as a store of potential wealth that can be sold later.

…but beware

Diversification of cash flows, not revenues, confers absorption. A collection of unprofitable subsidiaries resembles a group of drunks leaning on one another for support.

Source

Too big to fail

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Large firms can survive by off-loading operations and reducing head count in crises. Size also increases the odds the government, customers, or suppliers will prop up an ailing firm.

…but beware

Size can breed bureaucracy that impedes agility.

Source

Tangible resources

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Valuable resources such as raw material deposits, real estate, and so on serve as a store of potential value.

…but beware

These resources can reuse internal political struggles within a firm over the distribution of gain instead of an external focus on creating value.

Source

Intangible resources

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Brand, expertise, and technology can insulate the firm against changes in the market in the short and medium term.

…but beware

Overreliance on existing resources can lull executives and employees into complacency.

Source

Customer lock-in

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Switching costs prevent customers from easily jumping ship, buying a firm time when circumstances shift.

…but beware

Lock-in works both ways: existing customers can drag a firm down as well as buoy it up.

Source

Protected core market

Benefits from this source of absorption…

Barriers to entry in a core market provide a safe stream of cash to weather storms.

…but beware

Hiding behind barriers to entry can dull a firm's competitive edge and leave it vulnerable if the barriers fall.

Source

Powerful patron

Benefits from this source of absorption…

A powerful government, regulator, customer, or investor vested in the firm’s success can buffer it from changes.

…but beware

Powerful patrons have their own agendas and may force a firm to pursue objectives not in the firm’s interest.

Source

Excess staff

Benefits from this source of absorption…

The corporate equivalent of body fat, these employees serve as a store of value that can be shed in hard times.

…but beware

Excess employees depress profitability and create busy work for others. Worst source of absorption.

Managers build absorption capacity by stockpiling slack resources. In the 1960s, the sociologist James D. Thompson introduced the notion of buffering—activities intended to smooth or absorb environmental fluctuations. Thompson analyzed how manufacturing firms protected their core production capacity from fluctuations in demand by, among other things, maintaining large stocks of inventory and taking steps to smooth demand.4 Although holding large stocks of inventory has fallen out of favor as a buffering mechanism, firms continue to accumulate cash as a slack resource to hedge against unforeseen events. In contrast to specialized resources, like a brand or technology, cash is fungible—it can be deployed against most contingencies even if a manager cannot foresee its ultimate use.

Brazil’s regional jet maker Embraer, for example, used its cash-rich balance sheet to absorb the shock from 9/11, when its customers abruptly refused delivery of $500 million worth of aircraft in the span of a few months. European rival Fairchild Dornier, in contrast, had recently gone private in a leveraged buyout, and went bankrupt because it lacked the financial wherewithal to survive the precipitous fall in demand that followed the 9/11 attacks. Cash reserves are particularly important in turbulent contexts, such as emerging markets or new ventures, where the cost and availability of capital is subject to wide swings, and where funding is often most difficult to obtain just when a company needs it most.

Firms can accumulate not only spare cash but also employees. Over time, firms often build up “latent slack,” the academic euphemism for more employees than a company needs to get the work done. Although keeping these employees on the payroll shows up as a cost on the income statement, excess workers and managers represent slack resources that management can recover, through layoffs to free up cash in hard times.5 Corporate fat, like its human equivalent, serves as a store of energy that can be burned in hard times. Researchers have demonstrated that the benefits of latent slack are greatest when a firm enters a crisis with significant excess staffing and head count reductions are part of a broader restructuring effort.

Companies can enhance their absorption by locking up resources that are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate. Saudi Arabia’s state-run oil company, Saudi Aramco, controls approximately one-quarter of the world’s easily extracted oil reserves, a store of resources that enables the company to weather the shifting tides of prices, geopolitics, competitive dynamics, and fuel technology with relative impunity. Companies can also buffer themselves by controlling intangible resources such as a technology or a brand. Coca-Cola controls the most valuable brand in the world. The strength of Coke’s brand has allowed the company to survive slowing demand in its core market, aggressive innovation by competitors, tensions with bottlers, and turmoil among the top executives that resulted in a rapid turnover of CEOs. While Coke relied on its established brand, Pepsi proved more agile, seizing opportunities in bottled water, sports drinks, and juice that allowed it to overtake Coca-Cola in market capitalization in December 2005, for the first time in more than a century of competition.6

High switching costs can prevent customers from abandoning a supplier even when an attractive substitute arises or rivals offer better terms. Large corporations using Oracle database software face enormous costs, risk, and hassle to migrate systems to an alternative product. They tend to stay put, allowing Oracle to absorb shifts in technology, competitive dynamics, and customer preferences. In many cases these barriers to entry provide a profitable core business that serves as the basis for expansion into new sectors. Oracle has used cash from its database business to acquire applications-software makers such as PeopleSoft and Siebel, while Microsoft’s strong position in Windows and Office have underwritten forays into gaming. Few barriers to entry remain impenetrable in the long term, but they can buffer firms from onslaughts in the midterm.

Strong partners vested in a firm’s success enhance absorption. During the boom years in the personal computer industry, Microsoft had a strong interest in seeing Intel upgrade its microprocessors to run ever-larger versions of Windows, and both companies supported Dell as it tried to sell more personal computers with Intel and Microsoft inside. Government support is another source of absorption. Emirates Air, one of the fastest-growing major airlines in the world, benefited throughout the 1990s from a close relationship with the ruling al-Maktoum family of Dubai, whose interests in promoting their city-state are interwoven with the airline. Dubai has invested in the infrastructure to support Emirates’ growth, encouraged the development of attractions such as indoor skiing in the desert and Dubai World that attract passengers to fly to (and through) Dubai, and put in place policies (such as no personal income tax or labor unions) that helped Emirates attract employees and avoid the union strife, which hampers many airlines. These partnerships rely on the patron’s own absorption. A small city-state without significant oil reserves, Dubai itself possesses limited absorption to weather crises.

Low fixed costs also help a firm to survive unexpected shocks, such as price wars, higher raw material costs, and volume declines. The semiconductor design and fabricator Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has followed a relentless strategy of lowering fixed costs since its inception in 1987. In 2006 TSMC could break even at a capacity utilization of approximately 40 percent, while its three largest competitors broke even at approximately two-thirds capacity utilization.7 In practice, this meant that TSMC could maintain its profitability when volume dropped without resorting to low-margin business to fill its fabrication plants.

It is easy to underestimate absorption, which looks plodding compared to agility, but it is dangerous to do so. During World War II, the German army was one of the most agile fighting forces in modern history—by most estimates the typical German soldier was 25–50 percent more effective than his American or British counterpart.8 The German blitzkrieg was perhaps the best example of military agility in recent history. For all their agility, however, the Germans lost. The Allies’ greater absorption allowed them to deploy more troops and hardware, absorb the German forays, and ultimately prevail.

ABSORPTION AND STRATEGIC AGILITY

At first glance, absorption seems purely defensive, but companies can employ it to seize new business opportunities as well as mitigate threats. Firms that rely on absorption solely for defense risk falling behind rivals that use it as offense as well. For over a century, Banco Santander and rival Banco Popular belonged to a protected oligopoly of Spanish banks. When Spain deregulated its banking market, their paths diverged. Santander bulked up in Spain, seized opportunities in Latin America, and expanded into Europe, while Banco Popular played it safe, eschewed foreign markets, and stuck to its domestic market. Popular’s domestic focus provided good returns to shareholders but prevented the bank from absorbing changes—such as the housing slowdown in Spain—or acquiring major opportunities outside its home market.

Absorption is particularly valuable in supporting strategic agility, an organization’s ability to spot and decisively seize game-changing opportunities that arise out of turbulent markets. Carnival’s larger size and lower fixed costs helped the cruise line convince investors to favor it in the battle to acquire P&O Princess. A healthy balance sheet and geographical diversification of cash flows among his existing steel operations allowed Lakshmi Mittal to snap up the Kazakh steel mill and iron deposits.

Golden opportunities are not spaced evenly over time, and absorption can keep a company in the game until its big chance emerges. Apple’s iPod is the stock example of agility. The iPod is an excellent example of agility, but it was the firm’s absorption that kept Apple alive enough to seize the opportunity. During the 1990s, Apple was relegated to the “other” category in the PC market when its share fell to under 5 percent, and its stock remained flat from the late 1980s through early 2004. A small base of loyal customers kept the company in the game long enough for changes in the context to create a golden opportunity.

Absorption also allows companies to outlast rivals in wars of attrition. As Microsoft entered the video game industry, the software giant duked it out in round after round with Nintendo and Sony, losing billions of dollars by some estimates. But Microsoft has also built up enormous stores of absorption over the years—through customer lock-in, brand identity, and cash reserves—that allow it to wear down its gaming rivals through successive periods of investment. Microsoft’s absorptive capabilities increase the odds that the company will emerge victorious at the end of the battle for dominance in the video game industry.

While agility allows a company to stake out an early position, absorption allows it to reinforce an early beachhead. In the fast-moving consumer goods industry, both Groupe Danone and Procter & Gamble spotted opportunities in China, Russia, Brazil, and other emerging markets. Lacking absorption, Danone relied on joint ventures to scale quickly despite limited resources. This approach created headaches later on when the partnerships soured. By contrast, the more absorptive Procter & Gamble could afford to staff its emerging market operations with expatriates and then hire local talent and inculcate them in the P&G way over the years.

AGILE ABSORPTION

Managers often see absorption and agility as stark alternatives—the former the domain of established enterprises defending turf and the latter the realm of nimble start-ups looking to grow. Ali’s triumph in the Rumble, however, demonstrates the power of combining the two. Ali’s training regimen months before the fight consisted of being clobbered by the hardest-hitting sparring partners he could find, to increase his ability to take a punch. During the Rumble he unveiled the now-famous “rope-a-dope” strategy, deliberately placing himself on the ropes to channel the energy of Foreman’s blows and allow Ali to absorb more punishment.

Absorption and agility are complements, not substitutes. They resemble yin and yang, the two opposing but complementary forces that coexist in all living things, according to traditional Chinese philosophy. Yin, the passive element, corresponds to absorption, while yang is the active element, resembling agility. The balance between yin and yang is constantly shifting, and their effectiveness increases by getting the combination right, rather than relying too heavily on one or the other. Agile absorption refers to an organization’s capability to consistently identify and seize opportunities while retaining the structural characteristics to weather changes in the market. It is the organizational equivalent of Ali in his prime, fleet of foot and hand but able to take a blow.

To assess their organization’s level of agile absorption, managers can ask themselves a series of questions: “How agile are we? How absorptive are we? Where does our absorption currently come from? Are these the best sources? Are there alternative ways to boost our absorption that would enhance our agility?” They can also inventory the levels of agility and absorption within their organizations with the survey at the end of this chapter.

At first glance, the structural factors that provide absorption appear incompatible with agility: global scale versus a lean operation, for instance, or legacy assets versus a clean sheet of paper. In fact, however, leaders can achieve and maintain agile absorption, as the examples below illustrate.

More good fats, fewer bad fats. As a first step, executives should recognize that sources of absorption vary in their effect on agility. Like dietary fats, all sources of absorption provide energy for hard times, but some sources are healthier than others. Low fixed costs, for example, are an outstanding source of absorption. They allow a firm to weather a wide range of threats without degrading the ability to seize opportunities.

Other sources of absorption, in contrast, come at an unacceptably high cost in terms of foregone agility. Excess workers, particularly those in staff positions, tend to generate work to justify their existence. Their efforts, however well intentioned, introduce unnecessary complexity and bureaucracy that sap agility. Powerful patrons can drag an organization down as well as lift it up. Government interventions saved many banks, but their salvation comes at the cost of political interference with strategy and pay policy. The government of Dubai might encourage Emirates to grow at a pace that serves Dubai but causes the airline to overinvest in capacity.

Actively manage trade-offs. Executives should manage trade-offs when balancing agility and absorption. Time and time again, General Motors missed opportunities that Toyota seized—for example, by differentiating on product quality and coming out with smaller cars and hybrids. Many factors contributed to GM’s decline, but one oft-cited explanation is management’s inability to lay off workers when demand slipped. Guaranteed jobs translate labor from a variable cost to a fixed cost, thereby decreasing absorption. Toyota also guarantees its employees lifetime employment; the Japanese carmaker attempted to lay off workers in the 1950s, but encountered massive resistance from unions and the government. Toyota traded the higher fixed costs for flexible work rules, variable job assignments, and employee involvement, which collectively enhanced the company’s agility. GM executives, in contrast, gave the absorption away without receiving agility in return.

Many managers believe that corporate bulk is the archenemy of agility. But it is complexity, not size per se, that smothers agility. Companies that pursue a focused business model, such as Wal-Mart, Toyota, or Southwest Airlines, can scale without adding complexity. This extreme focus comes at a cost, however, since it decreases the scope for portfolio agility and leaves a firm vulnerable to shifting consumer tastes (think Laura Ashley) or technologies (think Polaroid).

An alternative approach to achieve scale with agility breaks a large organization into multiple independent profit-and-loss units. Independent units can move quickly and maintain a sense of ownership among employees who might feel adrift in an organization with 200,000 employees. This approach offers the potential to combine operational, portfolio, and strategic agility with a high level of absorption. Firms that have excelled at managing multiple units in the past, such as GE, Johnson & Johnson, and HSBC, have remained industry leaders over extended periods. This approach carries costs as well: independent units often duplicate back-office functions, which increases fixed costs, and executives must invest heavily to promote cooperation among fiercely autonomous divisions.

Build an agile culture on an absorptive asset base. In his early career, Muhammad Ali could bob and weave to victory, but he rose to greatness by combining agility with absorption. Over time, however, the agility seeped from his limbs, and Ali survived his late fights through absorption alone. Many organizations follow a similar arc. Early agility wins them the trappings of success—size, cash, and a secure position. These sources of absorption, however, gnaw away at the cultural roots of agility. Bureaucracy, political infighting, complacency, and arrogance sprout in their place. When the context shifts—and turbulence ensures it will—the bloated organization lumbers through the ring like a punch-drunk heavyweight, absorbing blows it can no longer dodge and missing opportunities it is too slow to seize. The cumulative effect of these blows wears down champions, such as U.S. Steel or General Motors, two companies that once appeared invincible. A similar fate could undo absorption heavyweights such as Merck, Coca-Cola, Microsoft, Citigroup, Royal Dutch Shell, or Sony.

Tendency is not destiny. The decline and fall of a company’s culture of agility is neither inevitable nor irreversible. When Mittal acquired state-own mills in Mexico and Kazakhstan, the steelmaker built an agile organization on the absorptive infrastructure of these large facilities. Through subsequent mergers and acquisitions, Mittal has dramatically increased its absorption by bulking up in size, diversifying its cash flows, and acquiring technology. Through the process, however, Mittal Steel has remained more agile than competitors by writing agility software on the hardware of absorption. I hope that the insights in this book help managers throughout the world balance agility with absorption to seize the upside of turbulence.

CAN YOUR ORGANIZATION GO THE DISTANCE?

All organizations combine some degree of agility and absorption. Circle the number that reflects your level of agreement with each of the following statements for your own organization. When you have finished, calculate the average of your scores for both agility and absorption, then plot your score on the matrix to see where your organization falls.

FIGURE 11.2 Going the Distance Survey

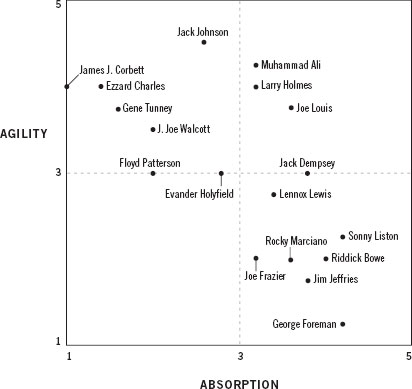

The survey allows you to assess quickly which heavyweight boxer your organization most resembles. The two-by-two matrix below plots eighteen of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time in terms of agility (including variables such as hand speed and footwork) and absorption (including size and durability). Foreman defines one extreme, scoring among the highest in absorption and lowest in agility. The 1892 heavyweight champ James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett represents the other, displaying exceptional agility but limited absorption. The boxers who scored well along both dimensions—including Joe Louis and Larry Holmes—are among the greatest of all time.

Using your survey data, plot your own organization in terms of agility and absorption to see which heavyweight boxer your organization most resembles.

FIGURE 11.3 Boxer Matrix