10.

AVOIDING A CORPORATE MIDLIFE CRISIS

Conventional management wisdom holds that companies, like people, must pass through a life cycle.1 Firms begin life with the rapid-fire experimentation of a start-up, scale the business during the corporate equivalent of adolescence, mature into the dull reliability of middle age, and lapse into inevitable decline. Sometimes companies progress through this sequence as a cohort. Minicomputer makers arrayed along Boston’s Route 128 and steelmakers in Sheffield, England, first rose and then fell as a group.2 Other times a company passes through the life cycle in isolation, as Polaroid or Laura Ashley did. Life cycle, according to this viewpoint, is destiny.

The corporate life cycle framework describes a common progression for many organizations. But life cycle is not destiny. Firestone declined, but its crosstown rival Goodyear survived the transition to radial tires. Brahma was already a century old when Marcel Telles took the helm. Other examples of long-established firms that have managed to renew themselves over extended periods include General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, HSBC, Nokia, and the Samsung Group. These firms, it seems, have found the corporate equivalent of the fountain of youth.

The secret to their success lies in a simple insight: companies do not pass through life cycles, opportunities do. Most firms, particularly large organizations, oversee a diverse portfolio of opportunities that exist at different stages in the life cycle. There are, of course, single-product companies that at first glance resemble one-trick ponies. Even then, a deeper look often uncovers multiple opportunities. Kodak, for example, is best known for its film business. But in the 1990s the company also had a vibrant medical imaging and clinical diagnostic business even after divesting operations in photocopying, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. There are no mature companies, only portfolios overloaded with mature opportunities. Organizations can avoid a corporate midlife crisis through portfolio agility—the ability to quickly and effectively shift resources, including cash, talent, and managerial attention, out of less promising units and into more attractive ones.

For many managers, journalists, and academics, diversification is a dirty word. Diversified conglomerates—think Daewoo and Tyco—are always a bad idea according to this line of thought. The litany of sins associated with diversification is long: it creates unmanageable levels of complexity, forces profitable units to subsidize the losses of less successful units, and complicates financial reporting. Managers diversify, according to this school of thought, for all the wrong reasons. By buying unrelated businesses, CEOs diversify their personal wealth tied up in company stock, entrench themselves in their position, and increase their power and prestige by controlling a sprawling empire.3 A series of empirical studies support the hypothesis that diversified firms destroy value.4 One careful study by Professors Philip Berger and Eli Ofek found that the average diversified firm destroyed 15 percent of the value its component units would have created as free-standing entities.5 Companies should stick to their knitting, according to this view, and allow investors to diversify their holdings by acquiring shares in a wide range of focused companies. Research in strategy encouraging firms to “stick to their knitting,” “focus on their core” reinforce the message that corporations should pursue extreme focus.6

This viewpoint ignores some inconvenient truths. Recent research by financial economists has found that diversification per se does not necessarily destroy value.7 The so-called diversification discount, these studies suggest, arises when managers diversify to escape problems in their core businesses. The resulting conglomerates often underperform because the component units earn low returns, not because they are diversified. Diversification also provides opportunities for growth. Recall the study of two hundred large enterprises that found that the reallocation of resources to faster-growing segments within a company’s portfolio was the largest single driver of revenue growth. Indeed, diversified firms such as Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, and Samsung Electronics have leveraged their portfolio agility to succeed over long periods, while private equity groups, including Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle, and TPG, have rewarded their limited partners richly by actively managing a portfolio of businesses.

A varied set of business units is necessary for portfolio agility but not sufficient. In the early 1980s, the conglomerate Westinghouse rivaled General Electric (GE), but in subsequent decades it faltered and was ultimately dismantled. Portfolio agility requires disciplined processes to evaluate individual business units and reallocate key resources such as money and talent. It is equally critical that the company as a whole, rather than individual units, control talent, cash, and other resources for redistribution. One North American bank paid a management consulting firm millions of dollars to profile its diverse business units in painstaking detail. The resulting research provided a compelling case for shifting resources from two of the established businesses into promising new ones. Unfortunately, the bank was a loose federation of units and lacked the precedent or processes to reallocate resources across fiefdoms. Despite the clear data favoring a reallocation of resources, the bank’s cash cows continued to hoard their money, their claims on the IT budget, and their best people, while the promising businesses withered, starved of the resources they needed to grow.

Portfolio agility demands that leaders make difficult and often unpopular choices, particularly when removing resources from a business or reversing previous commitments. The late Reginald H. Jones, Jack Welch’s predecessor at GE, had the formal tools to classify the company’s strategic business units but shied away from some difficult decisions, such as exiting the Utah International mining company deal, which he himself had advocated. Welch reversed Jones’s missteps, cleaning out GE’s portfolio in his early years on the job. More impressively, he also fixed his own mistakes, such as selling Kidder, Peabody & Company in 1994, when the acquisition, engulfed in trading scandals, did not meet expectations. Welch allocated resources based on logic rather than emotion. He invested heavily in GE Capital, although he did not always see eye to eye with the leadership of that business. Meanwhile, he fired the head of Kidder, even though he was an old friend.

Before reallocating talent across business units, a company must cultivate a cadre of general managers versatile enough to move from business to business. GE invests heavily in that group of managers, giving them P&L responsibility early on, rotating them through jobs and units, and offering them leadership training. Goldman Sachs rose from a second-tier investment bank with a few products in 1976 to a global leader across a highly diversified product range by the early 1990s.8 Critical to Goldman’s rise was the Investment Banking Services (IBS) unit, staffed with generalists who solicited new business and maintained client relationships. At that time, most investment banks encouraged employees to specialize in a sector, region, or specific product. Goldman’s IBS bankers, in contrast, were true generalists, and could therefore move from one geography or sector to another as new opportunities emerged and others declined. Portfolio agility does not mean everyone in an organization will become a general manager. In fact, generalists allow others to increase their specialization. Goldman research analysts and product specialists could build deeper expertise in a sector or financial instrument, because they knew the IBS bankers could bridge their expertise with the client’s needs.

To achieve portfolio agility, leaders should view their organization as an array of opportunities at various stages in the life cycle, paying particular attention to promising opportunities. To avoid the corporate equivalent of a midlife crisis, they should recognize common portfolio pathologies, such as the use of the same metrics to assess opportunities at different life-cycle stages or the systematic failure to exit declining units. Only then can they manage their entire portfolio more effectively, seeding and nurturing the right opportunities while exiting those that drain valuable resources.

MAPPING THE FOUR LIFE CYCLE STAGES

The first step in managing a portfolio of opportunities is to map them. The standard method for evaluating a firm’s portfolio is to array them using a matrix, such as the Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) popular growth-share matrix.9 This matrix assumes that success results from increasing volume of products sold to build experience in the sector and scale economies. The BCG matrix focuses on market share and growth, two variables that directly drive volume. The simple matrix provides executives with a snapshot to compare “cash cows” that could fund investments in rising “stars,” while avoiding “dogs” and puzzling over “question marks.”

Portfolio planning using the BCG and related matrices took hold in many companies, but subsequent research found little evidence that these tools improved performance.10 Portfolio matrices suffer from two major limitations. First, they provide a static picture that fails to convey how a business unit might evolve over time. Lacking a sense of time, they also omit the critical inflection points as an opportunity passes through the life cycle. In pursuing the opportunity to sell My M&M’s, which customers personalize with their own message, executives at Mars had to navigate difficult questions as they moved from one stage of the life cycle to the next: Should they scale this product instead of other promising opportunities? How would they integrate My M&M’s with established businesses? A static model neither raises nor answers these questions.

An alternative approach to mapping a portfolio begins by disaggregating an organization into components that correspond to opportunities, recognizing that they vary by stages in the life cycle. Projects in the start-up phase, for example, are often formal development initiatives or skunkwork efforts flying beneath the radar. Mature opportunities are often business units with their own profit-and-loss responsibilities. Opportunities also vary by industry. In the fast-moving consumer goods industry, opportunities typically cluster around brands within specific geographies. Professional service firms view opportunities as distinct client offerings. The opportunity life cycle framework can be used at various levels within a company to analyze business units or to disaggregate customers and products within a specific unit.

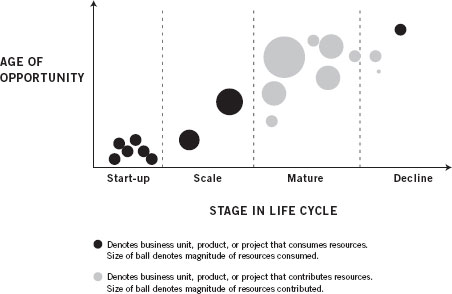

These opportunities can then be placed into one of four stages in the life cycle. (See figure 10.1.) Opportunities begin in the start-up phase when an entrepreneur or manager spots an unmet need in the marketplace and envisions a new way to meet the need. Like youth, the start-up stage is marked by constant experimentation to identify the best segment to target, or the right business model to create value. After validating the opportunity and stabilizing the business model, the opportunity enters adolescence and scales up to seize market share. Then comes maturity, in which the opportunity—now its own business unit—fights for market share against well-known rivals in a clearly delineated market. The final stage is decline, which can come about from a number of sources, including the entry of low-cost competitors, shifting consumer preferences, or the introduction of substitute products.

Opportunities consume different levels of resources depending on where they are in the life cycle. In the start-up stage, entrepreneurs or middle managers can tinker with an idea for years without spending serious money, but rapid growth during the scale stage often demands significant investment. Mature opportunities generate the cash to support their own operations and also fund start-ups and scaling businesses. Units in decline, if unchecked, can consume a disproportionate share of resources, management time, and emotional energy. Different opportunities can be denoted as balls that vary in color—black when an opportunity consumes cash and gray when it throws off resources. They also vary in size depending on the magnitude of resources they consume or generate.

FIGURE 10.1 Life Cycle Portfolio

The balls can be placed in the appropriate stage in the opportunity life cycle to present a snapshot of a portfolio at a point in time. The vertical axis plots the elapsed time from an opportunity’s inception to the present, and the horizontal denotes stage in the life cycle. In this graph, opportunities typically follow an upward-sloping line from young experiments (bottom left of figure) to old, declining businesses (top right). The stages in the life cycle convey an implicit sense of progress over time as an opportunity passes from one stage to another. Plotting actual opportunities against expectations reveals outliers. These outliers, in turn, raise questions that can focus attention on potential issues in the opportunity portfolio. (See figure 10.2.)

FIGURE 10.2 Outliers Raise Questions

Denotes business unit, product, or project that consumes resources. Size of ball denotes magnitude of resources consumed.

Denotes business unit, product, or project that contributes resources. Size of ball denotes magnitude of resources contributed.

The easiest way to map an opportunity portfolio is to start with financial resources. The operating cash flows consumed or produced by an opportunity in a year determines its size. The basic plotting can be refined in several ways. Managers might plot the net present value of the opportunity to determine the size of the ball. Further refinements include the scoring of opportunities by risk, shadow circles to denote their potential magnitude, and arrows to indicate the speed at which opportunities move from one stage to the next, relative to initial forecasts or industry averages.

This first-cut analysis provides the basis for plotting nonfinancial resources, which vary by industry, and might include engineering hours, production capacity, or information technology resources. The allocation of management talent across opportunities is an important consideration in almost all situations. One global engineering firm identified its twenty most promising managers and marked their initials on the opportunities they managed. All but two of those high-potential individuals were running mature businesses or staunching the bleeding in declining operations, leaving second-string managers to scale the opportunities crucial to the firm’s future health. None of these refinements will work in every situation, but they do suggest ways to extend the tool to deepen executives’ understanding of portfolio dynamics. Figure 10.3 provides a blank template to conduct a quick diagnostic of your own organization’s opportunity portfolio.

FIGURE 10.3 Plotting a Portfolio

Business opportunities typically progress through four stages—start-up, scale, mature, and decline—which are labeled along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis denotes the age of an opportunity, and the expected trajectory for an opportunity over time is shown as the upward-sloping dashed line. The balls represent different opportunities, with the size of each denoting the amount of cash consumed (black) or generated (gray) in a year. By mapping an organization’s constituent opportunities, managers can identify imbalances and other trouble spots, and surface important questions about opportunities that deviate from the expected trajectory.

COMMON PATHOLOGIES

The point of the mapping exercise is not precision, but rather to surface important questions. Are resources currently in balance? Can the mature opportunities fund all the start-up and scaling activities being undertaken? Are there enough or too many early-stage start-ups? Is a core business about to enter a period of decline? Portfolio imbalance is often a symptom of a deeper pathology in how resources are allocated within the firm.

No exit. Professor Joseph Bower and a series of his doctoral students have shown that in most large, complex organizations, resources are allocated through a bottom-up process.11 Frontline employees closest to the market identify and experiment with potential opportunities at little cost to the organization. To secure the significant resources required for scaling, a well-regarded middle manager must sponsor the project, take responsibility for its execution, and vouch for its ultimate success to senior executives and the board of directors. The middle manager puts her reputation on the line, providing a strong incentive for her to advance only the most promising projects and make sure they deliver.

This bottom-up process of resource allocation promotes investment, but often stalls in reverse because it fails to trigger disinvestment from opportunities that are not panning out.12 Managers rarely recommend killing a project that might jeopardize their own reputations or that of their colleagues. The cost of delaying exit from a declining business can be significant. Recall that the losses from Firestone’s delay in closing its outdated plants exceeded the cost of the Firestone 500 recall. Delayed exit diverts management attention, as senior executives spend so much time discussing problem children that they lose focus on promising opportunities. When companies allocate their best managers to fix their worst problems, they burn out the most rising stars and deprive them of the chance to scale an attractive opportunity.

The no-exit syndrome is a particularly thorny challenge in the scaling stage. Companies allow opportunities to consume resources even if they fail to gain traction in the market. Like airplanes that taxi beyond the runway without taking off, these businesses advance at high speeds, knocking down trees and buildings along the way. Because opportunities in the scaling stage devour so many resources, they live in the corporate spotlight, increasing the reputational damage their management champions incur if they pull the plug. Managers can smother start-up projects, but killing a project, burning resources to scale, often ends in a public execution.

One European financial services firm tackled the no-exit problem head on. When the CEO appointed an executive to scale an exciting opportunity in Eastern Europe, he also built in checks to ensure that it was possible to kill the initiative if necessary. He insisted the team include senior members from the risk and finance functions to oversee performance against plan. He refused to authorize the expenditures until the group articulated a handful of deal-killer indicators that would constitute clear grounds for terminating the business. He also structured the business as a separate legal entity, even though the firm owned all the shares. This legal structure allowed him to appoint a board of directors, which the CEO staffed with outsiders detached from the business, as well as a director who had scaled a service business and could distinguish typical growing pains from serious problems. When the risks of the new opportunity proved to outweigh the rewards, the CEO orchestrated a face-saving exit for the executive, promoting him to a significant position in the core business and praising his willingness to take on the scaling of a venture in an unfamiliar market.

Overvaluing value-based management. Finance theory instructs executives to invest only in projects that have a positive net present value and return surplus cash to investors. Value-based management puts a premium on credible forecasts of cash flow. The most credible forecasts are those based on low-risk projects in known domains that produce positive cash flows quickly. An investment process that values credibility and low risk above all else will penalize projects with uncertain outcomes, even when they offer a substantial potential upside.13

Blue Circle Industries, at one time the global leader in the cement industry, exemplified the benefits, and also risks, of putting too much value on value-based management. It adopted tough annual targets for return on capital employed (ROCE) backed up with business-unit budget contracts and incentives linked to increasing returns on capital. Blue Circle’s corporate office ranked potential investments according to prospective net present value, payback, and return on capital. Only those at the top of the list won approval, while those at the bottom were rejected—a break from a past in which interesting projects received token funding to encourage low-cost experimentation. Measured by ROCE, the approach worked. In the second half of the 1990s, Blue Circle’s return on capital doubled, producing cash to buy shares back.

But then the competitive landscape shifted. The industry began to consolidate globally, and emerging markets offered some of the juiciest opportunities. Because its capital budgeting process favored reliable cash-flow forecasts, Blue Circle turned down nearly all projects in emerging markets to focus its investments in stable countries with reliable prospects. The insistence on sure-thing investments left Blue Circle a laggard in the race for globalization. Despite a desperate bid for expansion in Southeast Asia in 1997, the company was overtaken by more aggressive competitors, such as CEMEX. It was acquired by Lafarge in 2001.

When executives wake up one morning and realize their organization lacks attractive opportunities for growth, they often attempt a crash course to renew the portfolio through large-scale initiatives, including unrelated acquisitions, large mergers, or a flurry of new products. Like most actions born of desperation, these have a high failure rate. A better approach ensures that the organization has a set of promising new opportunities in reserve, waiting for the day when circumstances favor scaling.

The Beta Group, a business incubator that commercializes promising technologies, evaluates many potential opportunities, sorting them into three categories. Ideas with no real promise land in the Dumpster; those ready for prime-time scale, and promising ideas whose time has yet to come are stored in a “refrigerator.” Promising start-ups can be premature for any number of reasons—perhaps the current market is too small, the technology has major kinks, or the business model is unclear. Beta’s approach enables the firm to focus its limited resources on two or three opportunities that are ready to scale, while keeping track of the fifty or so refrigerated projects. A company can keep tabs on such proposals by reassessing their viability, perhaps through small-scale experiments or joint ventures to obtain information on how those opportunities are evolving.

Maintaining a healthy stock of opportunities requires active leadership. Even during periods of restructuring and ruthless cost cutting, senior management must nurture promising businesses by providing political cover, framing the opportunities as experiments, or protecting them from corporate antibodies. They must also remain on the lookout for growth even in downturns. The best opportunities often arise in the worst times, as distressed sellers offload assets at bargain basement prices.

Let a thousand flowers bloom. Sometimes the problem is not too few opportunities but too many. At one fast-moving consumer goods company, the top managers mapped their portfolio to understand why significant investment in innovation had yielded disappointing returns. What they found surprised them. The company excelled at identifying promising opportunities, and managers agreed it was reasonably easy to find the resources to scale projects. But of more than a dozen opportunities that the company was funding, most had been scaling for longer than projected without gaining traction in the market.

The root problem was the ad hoc process the company used to select which opportunities received the resources required to scale. Managers aimed for fairness in allocating cash and talented people, but that egalitarian spirit meant the company gave the green light to numerous projects. Indeed, it was attempting to scale more than three times as many opportunities than its main competitor. As a result, none of those projects received the resources required to scale successfully, and they stalled in the market, much like the initiatives at 3M discussed earlier.

One size fits all. Projects at various life cycle stages differ in their objectives, optimal management style, performance metrics, and predictability. A start-up venture works best with an entrepreneurial manager seeking to validate the opportunity and stabilize the business model. Projects’ success should be evaluated against milestones tailored to their specific opportunities—number of users for a social Web site, for instance, or beta customer satisfaction for an engineering solution. A mature business, in contrast, requires an active steward focused on generating cash. (See figure 10.4.)

FIGURE 10.4 Managing Across the Life Cycle

Opportunities at different stages in the life cycle require different management approaches and performance metrics, and vary in terms of their predictability. Specialized institutions have evolved in capital markets to focus on these different stages. Man y companies, however, attempt to apply a one-size-fits-all approach to managing opportunities through the life cycle.

Objective

Start-up

Validate opportunity

Scale

Scale business model

Mature

Produce cash

Decline

Reinvigorate or exit

What motivates managers?

Start-up

Passion for idea

Fun and excitement

Recognition

Scale

Share of upside

Satisfaction of building something

Mature

Security of working in an established business

Autonomy

Power

Decline

Pay and bonuses for making tough decisions

Who are the best managers?

Start-up

Scientists and inventors

Entrepreneurs

Scale

Experienced builders with clarity of focus and drive to execute

Mature

Active stewards adept at spotting and neutralizing threats to core

Decline

Turnaround artists who are relentless in instilling financial discipline

Which metrics measure progress?

Start-up

Milestones marking specific achievements (often measuring customer adoption)

Scale

Focus on growth and time to profitability

Mature

Numerous metrics, typically refined and financial, often extrapolated from the past

Decline

Measures of cash released from terminating money-losing activities

How to secure or release resources?

Start-up

Spread passion for opportunity

Bootstrap

Limit resources required

Scale

Build enthusiasm with exciting growth story

Generate fast profits to protect business from skeptics

Mature

Generate cash to fund growth elsewhere

Protect the core business from any threats

Decline

Prune resources to fund growth elsewhere

Predictability (1 low to 10 high)

Start-up

1–3

Scale

4–6

Mature

6–8

Decline

8–9

Financial institutions that specialize

Start-up

Angel funding

Incubators

Early-stage venture capital

Scale

Venture capital

Mature

Banks

Public equity markets

Decline

Leveraged buyout firms

In 1999, IBM created the Emerging Business Opportunity (EBO) management system to spur organic growth and protect new opportunities until they were mature enough to stand on their own. EBO drew on a “horizons of growth” model that distinguished between opportunities in the start-up phase, those scaling through rapid growth, and mature businesses.14 IBM recognized that different growth horizons required distinct approaches to people, strategy, resource allocation, and measurement. The EBO was designed to protect nascent opportunities and identify when they were ready to move from one stage to the next.

EBO’s approach to measurement went beyond financial metrics to include milestones appropriate to each stage. Start-up opportunities, for example, might need to win a share of mind, as evidenced in press and analyst reports. Scaling businesses needed to demonstrate progress in trials and early-customer adoption, while mature businesses were measured against strict profitability and sales-volume objectives. The milestones helped executives spot when an opportunity was ready to move into the next horizon, perhaps requiring a change of management as well as different forms of support and incentives from EBO.

Generation gap. The final pathology has little to do with process and everything to do with people. Just as opportunities pass through life stages, so do the people behind them. Across a wide range of organizations, portfolios have decayed when executives gripped the reins of power for too long, blocking up-and-comers from positions of authority. Veteran executives often lack the urgent personal incentives to renew the opportunity portfolio—it is much easier for them to rest on their laurels and bide their time until retirement. When a cohort of seasoned executives have control over which opportunities to scale, they may err on the side of loss aversion, protecting the mature businesses (which they often scaled and ran) while avoiding risky bets on the future. “There are no mature businesses,” Warren Buffett once observed, “only mature managers.”

To avoid this fate, companies can empower younger managers who have a large stake in the future, as Brahma did with its trainee program. When the forty-seven-year-old John Browne became BP’s group CEO in 1995, he set out to place operating power in the hands of the next generation. He and his team broke BP’s bureaucratic organization into approximately 150 business units, each overseeing an oil field, a chemical plant, a regional marketing area, or other operation. Browne then handed the keys to these businesses to a new generation of managers, most of whom were in their thirties or early forties. This was a massive transfer of power because those operations collectively generated upward of $120 billion in revenues by 2001 and employed more than one hundred thousand people.

What to do with the heroes from the last war? In many organizations, the biggest obstacle to a generational shift comes from seasoned executives who want to maintain an active role. At BP, many of these leaders became group vice presidents, positioned between the 150 business units and Browne’s team. These senior executives coached the next generation, oversaw talent development and succession planning, and negotiated performance contracts with the business unit leaders. This structure left Browne and his team free to focus on branding, the company’s stance on environmental issues, geopolitical shifts affecting supply, and other larger, longer-term issues.

According to conventional wisdom, companies resemble organisms that must pass ineluctably through the predetermined stages of start-up, scaling, maturity, and decline. In large, complex organizations, things are not so simple. Business opportunities, not firms, pass through these stages. Most organizations include multiple opportunities arrayed across the different stages of the life cycle. Leaders who understand this distinction can enhance their organization’s portfolio agility and thrive in turbulence.