8.

THE AGILITY LOOP

What makes an effective leader in turbulent markets? Many think the secret of effective leadership lies in brilliant strategic insight—the intellectual horsepower to craft a clever strategy. Others stress discipline, believing that superior leaders excel at execution. Still others feel that a great leader is, above all, inspirational—capable of uniting an organization around an exciting vision. Some, and Dilbert comes to mind here, dismiss the phrase “effective manager” as an oxymoron.

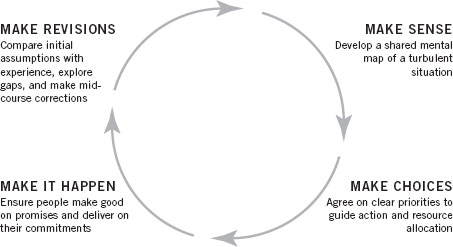

Leadership, at its heart, consists of getting things done through discussions with other people. Several studies find that executives spend between two-thirds and three-quarters of their time engaged in discussions—formal and informal, short and long, one-on-one and in groups and increasingly through e-mail.1 In this chapter, I introduce the agility loop as a framework to help managers structure and run discussions more effectively. Like the OODA loop or Popper’s experimental cycle, the agility loop emphasizes iteration and consists of four steps required to advance into an unknowable future: making sense of a situation; making choices about what to do, not do, and stop doing; making things happen; and making revisions based on new information.

The loop can be embedded within formal processes (strategic planning, budgeting, resource allocation, or performance management) or within the informal conversations—including chance encounters at the water cooler—that fill out the typical manager’s day. No organization can achieve agility if these discussions are concentrated at the top of the company; they must be distributed throughout the organization.

All too often conversations bog down in an endless series of unproductive meetings in which the usual suspects cover the same ground without forward progress. Frustration mounts as participants spin their wheels or talk in circles. Discussions frequently stall when managers lead the wrong kinds of discussions at the wrong time (see box). Although each type of discussion is simple in principle, in practice they break down when people lose sight of what they are trying to achieve, set the wrong tone, lack the appropriate data, or fall prey to common pitfalls.

FIGURE 8.1 The Agility Loop

BEFORE YOU CALL THAT MEETING

The first step in leading through the agility loop is deciding which discussion to have when, who should be involved, and how to lead it. The following simple questions can help improve the quality of discussions.

- What will we talk about? This simple question often surfaces a disturbing lack of focus about the objective of a discussion.

- Are the right people in the room? Discussions to make sense of a turbulent situation work best when outside viewpoints (from customers or regulators, for instance) are brought to bear, while execution requires that the people who will do the work—rather than their boss or colleague—be in the room.

- Are we talking about the right thing right now? Managers must make a call on what conversation is appropriate for the current situation. Are people rehashing assumptions when they should be executing agreed priorities?

- Does the conversation have the right tone? Leaders must understand what an effective discussion sounds like at each step. They should establish and maintain a spirit of open inquiry while trying to interpret an ambiguous situation, for example, and promote respectful arguments when making hard trade-offs.

- Are we skipping key conversations? Managers must ensure that they are having all the conversations they need. Leaders with a bias for action often shortchange sense-making in their haste to do something, while more cerebral executives may overanalyze strategic issues without ensuring execution.

DISCUSSIONS TO MAKE SENSE

Discussions to make sense should produce a shared mental map of a situation. These conversations should be based on data, specifically information that is real-time, unfiltered, shared, and holistic. Recall that Zara design teams made sense of the fast-moving fashion scene, in large part because they collected both quantitative and qualitative data from the stores daily, shared that information, and considered information not only from a single store but also from the country and world markets to get a fuller picture and spot emerging trends. Absent good data, people default to preconceived notions and ungrounded assumptions.

The best way to make sense of novel situations is to dig into data with an open mind. Unfortunately, participants often make up their mind about what is going on before the discussions begin, and advocate a preformulated point of view instead of exploring alternative interpretations. During the Cuban missile crisis, President John F. Kennedy tried to assess the situation afresh. His military advisors saw the missiles as a prelude to war. They advocated invasion, a course of action they had favored for some time, even though a military strike could escalate into nuclear war.2

A tone of open inquiry can minimize the tendency toward pre-baked interpretations. During his successful tenure as U.S. treasury secretary and earlier as co–managing director of Goldman Sachs, Robert Rubin analyzed new situations, from evaluating a risk arbitrage deal to managing an economic crisis, by pulling out a pad of yellow legal paper to write down a long list of questions.3 Many leaders, in contrast, affirm their authority by claiming to know the answer, no matter what the question. Soliciting questions allows participants to admit they don’t know everything, dampens the impulse to commit prematurely to an interpretation, and creates an opening to introduce difficult issues by posing them as questions.

In turbulent contexts, decision makers should avoid anchoring on a single interpretation of a situation. During the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy’s team nearly adopted the “obvious” interpretation that the missiles signaled an escalation of hostilities. In novel situations, however, the best interpretation is rarely obvious, and the most obvious one is often wrong. Participants must feel safe putting forth alternative interpretations. Leaders can stimulate different points of view, rather than passively waiting for them to emerge, by bringing outsiders or iconoclasts into a discussion. Kennedy invited Llewellyn “Tommy” Thompson, a former ambassador to the Soviet Union, who disagreed that Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev wanted to start a war. Thompson argued that the Soviet leader had backed himself into a corner and was seeking a face-saving way to deescalate the tensions—an interpretation the generals dismissed, but which proved accurate. Kennedy also demanded his advisors generate alternative interpretations and actions, a demand that made it safe to discuss the “soft” options of blockade and diplomatic negotiation that allowed both sides to avoid escalating the conflict

Managers sometimes appoint a devil’s advocate to stimulate alternative views. Fierce criticism is a mistake at this stage in the agility loop. Tom Kelley, the general manager of the influential design house IDEO, argues that devil’s advocates “may be the biggest innovation killer in America today” because they nip promising ideas in the bud.4 A fledgling mental map will raise more questions than it can answer initially, but that does not mean it is useless or wrong. Adlai Stevenson, then the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, viewed the Cuban missile crisis through a diplomatic lens, and favored negotiating with Khrushchev. Kennedy’s hard-line advisors savaged Stevenson’s view, but the president came to recognize the value of a deal with the Soviet Union as part of his approach to defusing the crisis. A devil’s advocate with the license to savage new interpretations can smother discussions to make sense, although this role can enhance discussions to make choices and revise an existing mental map.

Empathy is one of the most critical yet overlooked aspects of making sense. Empathy is not niceness, often used as an excuse to avoid difficult discussions, but rather the ability to see a situation from another person’s perspective. Empathy can offset the tendency to see the “other” in abstract terms. Many of Kennedy’s advisors believed the Soviets understood only power and respected only force. Because he knew Khrushchev personally, Thompson was aware that the Russian leader despised war. Thompson thought not about what the Soviets would do but what Nikita Khrushchev would do.

In corporations, the “other” often includes competitors, regulators, nongovernmental organizations, and customers. When helping to vet growth opportunities for a large European bank, I jotted down the verbs the teams used to describe what they would do to (not for or with) “the customer,” which included “cross-sell,” “leverage,” “squeeze,” “exploit,” and “penetrate.” At this point I interrupted the proceedings to ask how many customers went to the bank hoping to be “exploited” or “penetrated.” This lack of empathy for customers is depressingly common—one leading technology firm referred to customers as “sockets,” presumably just waiting to be plugged.

In their haste to do something, teams shortchange discussions to understand what is happening. A bias for action is invaluable in execution but can short-circuit clarifying discussions. Take-charge or gung-ho managers who pride themselves on getting the job often dread the thrashing around necessary to understand a turbulent market. To avoid the ambiguity, they dive into the details of implementation and bypass sense-making discussions altoghter. When action proposals arise, it is best to dig backward to unearth and examine the assumptions that underlie a plan of action. Helpful questions include “If that’s the solution, what exactly is the problem?” and “What fresh data would convince us that our interpretation is wrong?”5

Executives can separate discussions to interpret a situation from deciding what to do. The top management team of Diageo Ireland breaks the monthly performance management process into distinct meetings.6 On the second day of the month they assess the market situation and identify potential issues. Five days later, they decide what to do. A leading professional services firm follows a similar logic by considering important issues in three conversations: the first, to discuss alternative interpretations of the situation, the second, to debate a set of alternatives, and the last, to decide on a course of action. Discussions to make sense should answer the question “What is going on here?” while discussions to make choices address “What should we do?” Collapsing them into a single conversation degrades the answer to both questions.

DISCUSSIONS TO MAKE CHOICES

Discussions to make choices aim toward agreement on a small set of clear priorities that focus organizational resources and attention on opportunities that matter most. In turbulent environments, a constant deluge of potential opportunities and threats creates an urge to hedge bets against every foreseeable contingency. Ironically, the spread-your-bets approach increases rather than decreases risk by wasting resources on skirmishes that mean little and by depriving key initiatives of the funds and people they need to succeed. Conversations to make choices conclude when a team agrees on a set of priorities that are consistent with its mental map and concrete enough to guide action and resource allocation throughout the organization.

These conversations are about making difficult trade-offs, and they must allow hard-hitting discussion where team members express disagreements and reservations. Without active efforts to stimulate debate, these conversations drift toward superficial agreement, with unresolved conflict lurking below the waterline. Candor in debate must be tempered with respect for the individuals. When proposals are personalized—“Jane’s idea” or “Jack’s recommendation”—it is difficult to reject an alternative without bruising the ego of the person who proposed it.

Groupthink occurs when a team converges on a single course of action, and the risk is acute when teams face time pressure and high stakes. Alternative options are not a luxury, however; they are a necessity. During the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy’s advisors quickly converged on military intervention, but the president demanded alternatives. Hard-liners considered these alternatives a waste of time that distracted them from planning the military strike. In the end, Kennedy’s call for alternatives produced the blockade that bought both sides time and the diplomatic deal that allowed Khrushchev to save face while removing the missiles. Kennedy, by broadening beyond a single alternative, averted disaster. In her research on effective decision making in turbulent markets, Professor Kathy Eisenhardt found that top management teams did best when they considered at least three alternatives.7 Multiple alternatives increase confidence that all options have been explored, help to flesh out the full range of possible responses, and provide a fallback if plan A fails.

Discussions to make choices derail when people add priorities without increasing resources or eliminating existing activities. When managers evaluate initiatives in isolation rather than as part of a portfolio of activities, they proliferate priorities. Middle managers in one European engineering group tallied more than fifty so-called strategic priorities that had rained down on them from headquarters in a two-year period. Each goal was worthy, but collectively they overwhelmed local managers seeking clarity on what really mattered. While the corporate executives were quick to add new initiatives, they rarely killed old ones.

To avoid priority proliferation, managers can inject discipline into the prioritization process. At Diageo Ireland, for instance, issues are triaged into one of three categories: “soft” opportunities (or threats), which receive ongoing monitoring but no action; “hard” opportunities, which require immediate action and became a priority within the company; and “nonissues,” which are dropped from the agenda altogether. The management team at one technology start-up follows a simple rule: before adding a new priority, they eliminate existing objectives to free necessary resources.

Simple rules can prevent discussions from stalling in a futile quest for complete agreement. Consensus is desirable, but the process takes time, and the costs of delay sometimes outweigh the benefits, particularly in fast-moving markets. Eisenhardt’s research on successful decision making found that the most successful firms did not seek complete consensus, but neither did they veer to the other extreme and allow an autocratic leader to call all the shots.8 Instead, the most successful teams adopted a policy of “qualified consensus,” whereby they sought agreement until they recognized complete consensus was impossible, at which time they invoked a set of prespecified rules to break the deadlock. The team in one software company deferred to the functional expert (so the marketing vice president could break the deadlock on an advertising campaign) or they deferred to passion, where two passionate votes in favor outweigh three mildly opposed. The most effective rules are clear and agreed on by the team members in advance.

Teams can also adopt simple rules to guide the prioritization process when they find themselves inundated by alternatives.9 América Latina Logistica began as a privatized branch of Brazil’s freight railway. The new company had only $15 million for capital spending, while managers requested more than ten times that amount to offset decades of underinvestment under government ownership. To select from among countless capital budgeting proposals, management adopted a set of simple rules, including “eliminate bottlenecks to growing revenues,” “lowest up-front cash beats highest net present value,” and “reuse of existing resources beats acquiring new.” These rules helped the team prioritize requests.

Companies often dole out cash, attention, and talent equally across opportunities in a misguided effort to be fair and avoid conflict. The risks were summed up in a memo by a Yahoo executive, who criticized the company for spreading resources like “peanut butter across the myriad opportunities…[resulting in] a thin layer of investment spread across everything we do.”10 Companies sometimes confuse a lack of discipline in resource allocation with corporate entrepreneurship. For decades 3M was a byword for corporate entrepreneurship, and the company cultivated a fertile garden of more than a thousand projects.11 By the late 1990s, however, shareholder returns lagged behind the market. The smooth allocation of resources across opportunities ensured that the most promising initiatives received less funding than they needed to scale, while the worst received more than they deserved.

When an outside CEO joined the company from General Electric, he pruned 3M’s overgrown tangle of opportunities. He installed a process to collect data from more than seventy separate laboratories to create a centralized database of all initiatives, including costs, projected sales, risks, and time to market. A group of technical directors ranked projects, then a team of senior leaders from manufacturing, marketing, and product development led a second cull, which reduced the number of projects to approximately seventy-five. These were screened against promising technologies, including nanotechnology, fuel cells, and optical displays. Each project proposal had to discuss risks and cycle times and needed to document a potential market of at least $100 million in annual sales.

FORCING HARD CHOICES IN HARD TIMES

Good times generate abundant cash, which blunts the need to make hard trade-offs, and managers can get away with spreading resources evenly. In a downturn, when cash is scarce, managers should allocate resources with greater rigor. Unfortunately, many managers try to spread the pain of downsizing evenly, demanding an identical percentage reduction in head count or expenditures, for example, across all units regardless of their future potential.

A downturn provides an opportunity to force hard choices. Consider Nokia. After the Soviet Union crumbled, Finland suffered one of the worst recessions in its history, and Nokia, then a diversified conglomerate, faced financial distress. Rather than spreading cuts evenly, Nokia’s executives made the hard call to focus on the fledgling telecommunications business, while exiting other businesses accounting for nearly 90 percent of revenues.

The Nokia example illustrates important points about making hard choices during a downturn. First, managers must be willing to reverse past commitments. During the 1980s, Nokia executives bet big on consumer electronics, but when that bet did not pay off, the top team was willing to cut their losses to expand the much smaller mobile phone business. Second, Nokia’s executives recognized that focusing on telecommunications reduced the group’s diversification and exposed the firm to greater risk. To offset the loss of portfolio diversification, they diversified within telecommunications, supplying both handsets and infrastructure, for example, spreading across geographic markets, and achieving economies of scale.

A downturn provides an occasion to make difficult decisions and revisit existing commitments throughout the organization. After the dot-com bubble burst in 2001, Cisco suffered a sharp decline in sales. Cisco’s leadership responded by forcing hard choices at every level in the organization, including consolidating suppliers from 1,300 to 420, halving the number of channel partners, culling the bottom third of products, streamlining research and development projects, and sharply reducing acquisitions.

During the boom, Cisco middle managers enjoyed wide latitude to acquire start-ups, with the company snapping up two dozen in 2000 alone. During the downturn, Cisco tightened up the process, creating an investment review board that met monthly to vet acquisition targets. When proposing acquisitions, managers had to present detailed integration plans and personally commit to hitting sales and earnings targets for the new business.

DISCUSSIONS TO MAKE IT HAPPEN

Execution is critical, but the majority of companies struggle to translate strategy into action. Recent studies, including a survey of more than one thousand organizations globally, suggest that 60 percent of organizations fail to execute their strategy effectively.12 One of the most widespread obstacles to execution is the gap between the nature of work in turbulent markets and the techniques organizations employ to get things done. A century ago, much economic activity could be standardized and took place inside the bounds of a strict hierarchy. Ford Motor Company produced the Model T on an assembly line, with activities from production of components through distribution of cars taking place within the confines of the Ford hierarchy. Such work could be managed through power—employees followed the boss’s orders or left—and well-specified operating procedures.

In recent decades the nature of work in developed countries has changed along two dimensions. First, much of the standardized work has been outsourced, offshored, or embedded in software. The work that remains is emergent, where workers must exercise heads-up judgment in execution without guidance from detailed process manuals. Second, many activities take place outside a hierarchy of power. Workers must navigate their way through complicated matrices, alliances, outsourced service providers, and loosely organized supply chains. This is networked rather than hierarchical work. People must coordinate with others who do not report to them. Barking orders and relying on power to get things done doesn’t work in a networked world. One study estimated that workers who orchestrate emerging work accounted for 41 percent of the U.S. workforce in 2004 and for 70 percent of new job creation.13

While the nature of execution has changed, the tools to get things done have not. Many executives still default to issuing diktats and crafting standardizing process flows, even when power is hard to wield and processes impede flexibility. Recall the study that found investment in process improvement dampened innovation. Standardized processes facilitate high-volume routine activities, but they straitjacket emergent work—such as providing a unique customer solution, dealing with an unprecedented crisis, pursuing a one-off opportunity, or experimenting with a new business model—so critical for agility in turbulent markets.

A simple but powerful mechanism—the promise—provides an alternative way to execute without recourse to standardization or hierarchical power.14 Promises, or employees’ personal pledges within and outside an organization, confer flexibility. Employees can look for the best person to do a job rather than turning to the designated contacts regardless of their competence, interest, or availability. A partner in a large accounting firm working on the nationalization of a global bank could identify partners familiar with each of the bank’s global markets. Both parties can exercise creativity and flexibility in agreeing on terms that suit the specific opportunity. The accounting partners could jointly agree on how to structure the project and who would oversee each portion. People can renegotiate as new information arises or priorities shift. Renegotiating promises is not easy, but it is less disruptive than reengineering a well-oiled process.

People often take a legalistic view of promises, defining them according to deal terms, much as lawyers might focus on specific clauses in a contract. The discussions that keep an agreement alive are more important than the specific terms. Both sides must thrash out what the recipient wants and why, how the person making the promise plans to satisfy the request, and any constraints or competing priorities that could derail delivery.

When leading discussions to solicit, negotiate, and monitor promises, managers should maintain a tone of discipline by demanding explicit promises and holding people accountable for delivery. They should temper that discipline with support to ensure that the person making the promise has what they need to deliver. Support can take several forms. A bank president might, for example, authorize the IT department to hire additional engineers or take other projects off the to-do list. Promises have teeth to the extent they are well made. The best promises share five characteristics; they are public, active, voluntary, explicit, and they include a clear rationale for why they matter.

Public. The most effective promises are made in public, to increase the cost of wriggling out of them, and to help employees understand how initiatives relate to one another. When Akin Öngör took over as CEO of Garanti Bank, he noticed that managers often failed to deliver on their promises to colleagues. He published managers’ commitments in the company’s weekly newsletter, along with updates on their progress. At Mittal Steel’s Mexican plant, internal service agreements were posted publicly, including who promised what to whom by when. Public promises clear the fog of anonymity that surrounds collective commitments made to abstract goals such as “capturing synergies” or “filling the white spaces.” The person making a commitment has a name and face in mind when executing the agreement, and the recipient knows who is accountable to deliver.

Active. Misunderstandings often arise when people from dissimilar functions, markets, or business units try to achieve a meeting of minds on what needs to get done. Based on their divergent backgrounds, they may understand the same promise in very different ways. Active probing by both sides does not eliminate these miscues, but can surface them eariler. Back and forth discussions clarify requests and produce creative counteroffers when the original request is infeasible to achieve.

The Royal Bank of Canada builds active discussions into its system to monitor opportunities for revenue growth. The person responsible for each initiative actively negotiates the milestones appropriate to the specific opportunity, rather than promising to hit standardized success metrics. They might judge an e-banking start-up by unique visitors to the Web site and revenue growth rather than total profits. The managers meet regularly to discuss progress and to renegotiate as necessary, much as an entrepreneur might with a venture capitalist.

Voluntary. In many organizations, people feel compelled to comply with every request in order to maintain their reputation as a team player, please the boss, or simply avoid looking like a jerk. When the response to every request is yes, it counts for little. A responsible no, in contrast, often signals resource constraints or conflicting priorities. To offset the tendency toward a meaningless yes, managers should legitimize responses other than automatic agreement. One software executive gave his team a set of cards, most of which were marked “yes” or “counteroffer,” while three were marked “no.” Using those cards, team members could decline three requests per quarter, provided they explained their rationale to the whole team. Commitment-phobic employees will abuse a voluntary system, and keeping them on the team undermines the effectiveness of voluntary promises.

Explicit. A large hydroelectric engineering joint venture recognized the need for clarity of organizational promises. From its inception in 2000, Voith Siemens Hydro Power Generation battled upstart Chinese and Indian manufacturers at the low end of the market and established rivals, including GE and Alstom, at the high end. The company responded by offering integrated solutions—entire power houses, including turbines, generators, and other components. To seize these opportunities, managers needed to revise how employees in different disciplines, departments, and regions managed their promises. The CEO initiated a program to ensure that promises were explicit. Engineers in the various disciplines created and distributed a set of checklists to guide requests and promises. The checklists specified a handful of factors that had to be clear to both parties, including names, dates, underlying rationales for requests, and the skills necessary to get the job done. The engineers established periodic design freezes, during which they would check that everyone shared an explicit agreement on who was doing what by when.

Motivated. People often make requests without explaining why they matter, and the recipient struggles to understand why the work is important. The most effective promises are motivated, in the sense that the rationale for the request is clearly laid out and linked to organizational priorities. It can be cumbersome to explain how a specific initiative fits in the overall corporate strategy, but when people understand why their promise matters, they are more likely to execute it with vigor despite conflicting demands and unforeseen roadblocks. Armed with a clear understanding of the underlying rationale, they can exercise creativity in meeting the spirit of the request instead of blindly fulfilling it to the letter. The U.S. Marine Corps uses mission-based orders, which articulate what the commanding officer wants and why, and why this matters to his commanding officer as well. After providing clarity on what to achieve and how it matters, mission-based orders leave the how of implementation to the discretion of the subordinate officer.15

DISCUSSIONS TO MAKE REVISIONS

In principle, discussions to make revisions are simple: the team discusses what they expected to happen and what actually happened, explores discrepancies between expectations and reality, and adjusts their mental map accordingly. Many managers, however, skip discussions to make revisions. When things are working, they continue plowing ahead, following the principle “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” They keep their sights fixed on the future and dismiss reflection on the past as a waste of time.

Even clear failure often fails to spur revision of an existing mental map and the associated commitments. People fear that any analysis of what went wrong will degenerate into an exercise in doling out blame rather than distilling lessons. People feel threatened by the scrutiny of their actions, and tend to personalize feedback as criticism of their competence, judgment, or motivation. The blame game is common but not inevitable. Founded and staffed by fighter pilots, the consulting firm Afterburner applies an iterative model used by the U.S. Air Force to help companies enhance their ability to execute. To ensure an honest discussion while debriefing an initiative, Afterburner advocates a “nameless and rankless” discussion, where anyone can bring up any issue. Leaders start the meeting by acknowledging what didn’t work for them and inviting criticism from the other team members to set a tone of open discussion.16

A fundamental obstacle to revision is the mistaken assumption that a map is right and failure is attributable to unforeseen events or feeble execution. In a turbulent world, it is better to assume the map is wrong. The partners of ONSET Ventures, an early-stage venture capital firm, begin with this premise. They will not seek additional funding for a venture until its business model has changed at least once, nor will they hire a CEO until the business model has stabilized.

Leaders must balance perseverance with the critical distance required to examine and revise a map and the related commitments. Alternating between periods of heads-down execution and dispassionate revision can help manage the map paradox. ONSET’s partners meet regularly to pose hard questions about portfolio firms: “If this deal walked in fresh today, would we still invest? Have they delivered what they promised? Why shouldn’t we pull the plug?” Before and after these meetings to question the plan, partners support the portfolio companies wholeheartedly, but they periodically shift into revision mode to reexamine their maps.

ONSET partners have built in a system to balance commitment to a map with distance. Founders are long on commitment but often too mired in details to see the flaws in their plan. ONSET partners serve as mentors to help the entrepreneur revisit his or her assumptions. Even partners can fall in love with a deal and lose perspective, however, so their colleagues provide a backstop in the revision meetings. ONSET also invites outsiders, including customers and other venture capital firms, into the revision process. Late-stage investors describe what actions a start-up team could take—such as launching a prototype of the product, validating market size, or lining up early users—to increase its valuation in subsequent rounds. Figure 8.2 summarizes discussions at each stage in the agility loop.

Over a lunch in Qingdao a few years ago, I asked Mianmian Yang, then the COO of Chinese appliance maker Haier, what she looked for in a manager. She explained that most executives focus too much on IQ—intellectual horsepower—and EQ, or the ability to work with people. Both are necessary, she explained, but in turbulent markets such as China’s, great leaders differed from good leaders in terms of TQ—a leader’s tenacity quotient.

Leading discussions through the loop demands tenacity despite inevitable setbacks. A dogfight with fighter planes will be over in minutes, but organizational agility confers its benefits over decades. Tenacity is often equated with formulating a plan and then sticking to it doggedly; think of Jacob wrestling the stranger, holding on throughout the night. But this rigid tenacity, devoid of revision, often leads to disaster in a turbulent world. Leaders should instead aspire to flexible tenacity, which combines urgency in execution with adaptation as circumstances change. Instead of Jacob holding on throughout the night, leaders should emulate Hercules. The Greek hero grappled with Nereus, the old man of the sea, who while wrestling could change shape from lion to serpent to water to a tree. Hercules never let go, but he also adjusted his hold as Nereus shifted from shape to shape. In the end Hercules prevailed.

FIGURE 8.2 Discussions Through the Agility Loop

Make Sense

Develop a shared mental map of a situation

Make Choices

Agree on clear priorities to guide action and resource allocation

Make It Happen

Ensure people make good promises and deliver on them

Make Revisions

Compare assumptions with reality, explore gaps, and adjust the map and related commitments

Appropriate tone

Make Sense

Open inquiry

Make Choices

Respectful argumentation

Make It Happen

Supportive discipline

Make Revisions

Dispassionate analysis

Information support

Make Sense

Real-time, unfiltered, shared, and holistic data

Make Choices

Ongoing monitoring of the portfolio of priorities

Make It Happen

Monitor performance against promises

Make Revisions

Variance reporting to spot divergence between the plan and actual results

Required leadership traits

Make Sense

The ability to grasp the essence of a messy situation

Curiosity

Empathy to see other points of view

Make Choices

Decisiveness

Sensitivity to keeping the social fabric intact through hard discussions

Credibility to make the call

Make It Happen

Trustworthiness

Ability to excite the troops about ambitious promises

Drive to maintain a sense of urgency

Make Revisions

Intellectual humility

Sensitivity to anomalies

Common pitfalls

Make Sense

Advocating preexisting positions

Failure to see the situation from other viewpoints

Anchoring too quickly on one viewpoint

Bias for premature action

Make Choices

Personalize proposals

Fail to explore alternatives

Superficial agreement

Priority proliferation

Search for unobtainable consensus

Spread resources evenly

Make It Happen

Private promises

Passive agreement

Meaningless yes

Implicit agreements

What without why

Make Revisions

Skip altogether

Hold too late

Blame game

Killer questions

Make Sense

What fresh data would convince us our interpretation is wrong?

What is surprising?

What is changing?

What opportunities do we see?

Make Choices

What other options do we have?

What will we stop doing in order to free required resources?

Make It Happen

What did you promise to do?

What have you done?

What is hindering you?

Make Revisions

What did we expect to happen versus what really happened?

Why was there a difference?

What should we change?

Which commitments that worked in the past are holding us back now?