Chapter 16

Structuring the Service Function for Success

In This Chapter

- Seeking the perfect structure

- Doing teamwork

- Creating self-managed teams

- Making cross-functional teams work

What’s the best organization chart for a customer service department? Should the customer service department report to sales, operations, marketing? Should the customer service department include credit, billing, and technical support functions?

These are the piercing questions that inquiring minds want to know the answers to!

And we have the perfect answer—one—to all of these probing issues. . . .

It doesn’t matter.

Well, maybe that’s a bit flip. We should slightly modify our brief, wise-guy retort. . . .

Beyond Politics

Political issues like organization charts, department lines, and reporting relationships don’t matter when everyone in your company wants to give customers the best service possible.

At Your Service

Relationships between colleagues, information sharing, and a collective commitment to great experiences for customers matter much more than how departmental boxes line up on the organizational chart.

When your organization has truly committed itself to creating The Service Difference by continually generating Personally Pleasing Memorable Interactions for your customers it will manage to do so. No matter who reports to whom. Remember that our premise for this book is this: in order to thrive in today’s competitive market, you must view customer service as being a company-wide cultural issue. Not a departmental issue.

Quote, Unquote

Men are forever creating . . . organizations for their own convenience and forever finding themselves the victims of their home-made monsters.

—Aldous Huxley

If you turned here desperately looking for the ultimate customer service department design, relax. It doesn’t exist. And if it did, it would have very little to do with delivering great service. Organizational charts simply don’t impact a customer’s Instant of Absolute Judgment. Customers don’t know how your department or company is organized, and they don’t care.

Structural Integrity

While we won’t (can’t) give you a magic, or even recommended, formula for structuring the customer service function, we suggest that you think about the following.

How you structure the customer service function—who reports to whom in what department—likely depends on these factors:

- The available management time and talent

- The size and geographic spread of your organization

- The company’s history and culture

- The way information flows (or could flow if everyone made a genuine effort to share information, and the company’s technology supported the free-flow of information)

- The service needs of your customers

- The competitive forces trying to outdo your efforts

Let’s look at each factor in a little more detail.

Voice at the Table

We’re all for the trend in self-managed work teams. And we’re delighted to see fewer layers of paper-pushing, over-the-shoulder-watching, and bureaucratic supervisors breathing down the necks of people doing the “real” work of pleasing customers.

Quote, Unquote

There are no such things as self-directed work teams. A CEO sets the direction for the company and teams are given a charter as to what they have to accomplish. Self-managed teams are something else. Here the teams can figure out how they’re going to achieve their goals.

—Mark Sanborn, professional speaker

At the same time, Customer Service is such an important link to customers that it should have a strong voice in top management. So where the customer service function reports may be best served by whomever can best serve it.

In other words, a strong advocate and champion for bringing the voice of the customer to the executive table is really more important than the title of the executive in charge of customer service. VP Customer Service? Great! But it also could be VP of marketing, sales, operations, or whatever.

Again, the key is that information should be flowing across department boundaries anyway—all the way to the top.

At Your Service

Customer service deserves a prominent place at your company’s Table Where Big, Important Decisions Are Made. Tragically, we have seen many cases where people on the front-lines knew darn well about critical problems and customer dissatisfaction, or unmet customer needs, but those messages never got to the people at the top of the organization. The people who could really do something with that information simply didn’t have it, or didn’t realize its significance. Top management should feverishly seek and heed customer input. People responsible for customer service should passionately provide that to top management.

Here or There and Everywhere

The rallying cry of “close to the customer” may encourage distributing customer service functions geographically. If your customer needs differ greatly from region to region, you may find an advantage in decentralized, locally responsive service centers.

On the other hand, technology allows you to serve customers from the world over in centralized operations. We discuss this in greater detail in Chapters 20–26. The point here is that geography need not drive how or where you set up your customer service function.

Uniquely Your Company

Even in the very same industry, two companies of nearly identical size can operate very, very differently. We’ve talked at length earlier in this book about how people have distinctive personalities that you need to understand. Well, organizations have unique personalities, too.

Your company’s corporate culture, its personality, has three main factors:

- The traditions that are ingrained into “how things work around here.” In some companies, they are habits based on traditions or values established by one or more founders decades, or even centuries, before.

- The personality of current top management. The boss puts his or her thumbprints all over the organization. (Ever notice how in a company where the boss wears a bow tie, lots of folks seem to favor bow ties? A case for Mulder and Scully?)

- The external environment that affects how your company works. If your customers or competitors create a crisis, or at least the threat of one, your company’s culture is going to respond (or perish).

So where does the Customer Service department fit in? What business processes are contained in the Customer Service department? The answers come down to this question: What seems to make sense in your shop? And, of course, that answer will change now and then. So make the question:

What seems to make sense in your shop, at this time?

As your company restructures to respond to a changing world, it will likely reorganize functional divisions, reporting relationships, and so on. Here are three key concepts:

- Keep the overall focus on serving your customers.

- Keep the information flowing across departmental boundaries.

- Don’t worry about the internal machinations—things are going to change again anyway.

Dry Bed, Trickle, Fire Hose, or Flood?

How well—if at all—does information travel from one functional area to another in your company?

This is the most important question we’ve yet posed in this chapter. In a way, it’s the only one that matters. People often get hung up on organizational charts and department groupings, but what counts is getting information and work processes from over there (whether that’s an office down the hall, or halfway around the world) to over here in order to serve your customers.

You’ll get some important ideas in the rest of this chapter for nurturing colleague-to-colleague relationships and creating a flow of information that gets customers helpful information fast, regardless of the formal organizational structure.

Tales from the Real World

When preparing for a presentation to a national association, Don interviewed several people from the association about the challenges they faced. During the course of an interview, a woman described her company as “many smaller teams serving a big team.” We’ve read lots of management literature and attended many seminars, but that off-hand remark probably best describes the ideal way of operating in a company, no matter what its size.

Go Team!

If we had a dollar for each time the word “teamwork” showed up in an executive speech, a company newsletter, or training seminar, we could own both the islands of Bora Bora and Manhattan.

Teamwork is a wonderful concept. Right up there with Mom, apple pie, and Old Glory. But what does it mean? Really?

When thinking about teamwork, you really need to ask:

What kind of team did you have in mind?

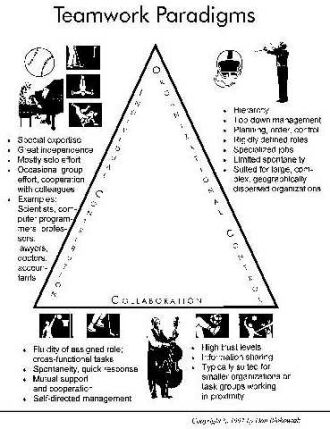

One of the reasons “teamwork” is an imprecise concept is because it can mean many different things. The following figure shows how teams can operate in ways that seem to be almost polar opposites.

Hut, Hut, Hike!

Consider football. Football certainly is a team sport. Yet it’s undeniably coach-driven; players follow a tightly prescribed play book and a highly defined game plan. The players on a football team work together, support each other, pull for one another. And they do that operating within rigidly defined roles (an offensive guard cannot go downfield or catch a pass!).

Football, by design, minimizes spontaneity from most players who operate within a tight physical and operational zone. Progress is measured in increments of three feet. It’s highly structured, highly regulated, and driven from the top-down (far more plays come from coaches on the sidelines than players on the field). Large, complex, and geographically spread organizations tend to follow the football model for their major corporate team.

Teamwork can follow many different models. When you say you want to “do teamwork,” know what you mean by the idea.

If sports metaphors don’t work for you, an equivalent can be found in the world of music. Football is akin to a symphony, with the conductor providing dominant, controlling leadership, and each member of the team playing a tightly defined—restrictive—role. Ever see a percussionist assume a piccolo player’s part on a moment’s notice?

Tales from the Real World

One of Ron’s clients is TeamCorp NFL, a private licensee of the NFL that produces teambuilding seminars for Corporate America. These seminars revolve around a skilled facilitator, NFL players, and coaches. The sessions facilitated by Ron have been extremely popular because the issues faced by a football team such as varying personalities, coaching styles, selecting good team players, and developing winning game plans are similar to the issues being addressed by teams in the business world. These seminars help companies achieve top results as football teams do—when the entire team is working like a well-oiled machine, where the players want to be on the team and are energized, and where the coaches are doing their jobs as leaders. Championship teams, whether they be in corporations or professional sports, cannot win the big game if the team is disorganized or dysfunctional.

Batter Up!

Contrast the football model with baseball. On the diamond, it is very much an individual’s game with bursts of tight coordination between teammates. It’s batter versus pitcher working with catcher, then batter versus fielder. An outfielder catches a ball all by himself, but the double or triple play requires the fast, highly skilled interaction of several teammates—each operating within a tightly defined physical and operational zone (like football).

Baseball is characterized by moments of solo performances backed by supportive colleagues, punctuated by lots of downtime between brilliant performances. Certainly, good coaching from the dugout and baseline contributes to both the success of individual players and the coordination of the team effort.

Again, music provides a roughly equivalent analogy. The soloist singer may be accompanied by instrumentalists, each playing their distinct parts, preparing and perhaps performing under the guidance of a musical director.

Many consulting, accounting, law, architectural, medical, advertising, design, engineering, and software firms follow the baseball model. So do academic institutions. These are teams of strong, specialized individuals mostly “doing their thing” with occasional collective, cooperative efforts with colleagues under the guidance of a knowledgeable leader.

Hoop It Up!

Contrast both football and baseball with basketball. Basketball teams operate with greater spontaneous interplay between players. Unlike football’s play book and baseball’s mostly stationary positions, basketball players are continually on the move. They’re constantly reacting to their opponents and interacting with each other.

While basketball players have assigned roles, they enjoy less rigidity and more freedom. The offensive and defensive roles may shift in a split second. While any player can score, a player may literally pass on the opportunity to get the ball to a colleague in a better position to score with less interference.

Just as players on the court constantly communicate with each other to maximize the opportunity of any given instant, so too are they in touch with the coach just inches away from the scene of the action.

Icy Teamwork

Hockey is something of a hybrid, blending elements of the other sports. It has basketball’s fast, spontaneous action, and an individual goalie with a fixed job and physical zone of operation. All it takes is for one player to not carry out his mission and the goalie has to step up and save the day by blocking a shot from the competing team.

Tales from the Real World

Wayne Gretsky, one of the best hockey players of all time, was once asked what the secret was to his great success in scoring goals. He claimed the secret was knowing where the puck was going to be before it got there. The only way Gretsky could do this was to anticipate future moves and have an instinctive feel for the moves of his fellow teammates.

The secret of a Great Customer Service Organization is anticipating both your customer’s potential problems before they arise and the skills your CSRs will need to deal with them. This way, your staff can be trained and ready to assist ably at what could be an Instant of Absolute Judgment.

A musical experience similar to the sports dynamics of basketball and hockey might be jazz. A jazz band plays music in a much freer form than the tightly regimented symphony, and with greater give and take between fellow musicians than typically found between a soloist and her accompanists.

Teaming for You

Which is the best model for teamwork? Better to ask:

What’s a team model that’s most appropriate to your mission and circumstances?

A football or baseball team is every bit as much a team using teamwork as a basketball team. They just do it differently. A team playing football couldn’t do it like a basketball team. The game doesn’t allow it. A football or basketball team trying to integrate the individualism of baseball would surely fail. And a baseball team trying to mimic basketball’s chatter, frequent movement, and interplay between teammates would likely miss more pop-up flies than it would catch as players ran willy-nilly across the field out of position and into each other. (By the way, this does occasionally happen, even in the big leagues.)

Winning Team Traits

All the sports team models share common characteristics:

- Competent players in assigned roles (with some that are clearly outstanding, but effective only as a member of a collective team)

- Commitment to success backed by hard work preparing and executing operating plans to meet objectives

- Appreciation by all teammates for every player’s assigned role

- Supportive cooperation between teammates

- Acceptance of personal accountability

- Acceptance of each team member’s strengths and weaknesses

- Acceptance and sensitivity to diversity related issues

- Quick reaction to unpredictable moves by competitors and opportunities that arise in play

The model that’s right for your organization may be none of the above. It’s probably a hybrid. On some tasks you play baseball—each CSR on the phone is a baseball player. On other tasks you’re playing football—determining refund or discount policies is a coach’s job. And yet on others, you’re playing basketball—such as collectively generating ideas for enhancing customer value through brainstorming sessions or cross-functional task forces.

Our goal here is to have you realize that teamwork comes in many shapes and sizes. And to get you to be aware of what kind of teamwork you have in mind when you talk about it or try to operate by it.

The value of even your best superstar can’t be measured only by individual output. It has to be gauged in the context of contribution to the team. Arguably, Michael Jordan is the greatest basketball player ever. But no matter how many points he scores in any game, he does it with the support of his teammates, and his team scores more because of his support for his teammates. Playing all by himself, the “Chicago Jordan” would never win a championship, maybe not even a single game. Even the most talented player can’t perform the jobs of the others on the team. While Hank Aaron hit all his record home-runs all by himself, he had the coaching and support of his teammates in practice. And he would have had a devil of a time covering the infield, the outfield, and home plate as a baseball team of one.

Tales from the Real World

On the Web page of Bourns, Inc. is this statement: “We know that Customer Service is not just a department in each division that receives orders and answers the phone. Every Bourns employee and Sales Rep provides customer service: whether they put epoxy on a part at a plant, pack units in a box to ship to the customer, review a customer drawing, quote a price or a delivery, answer a corrective action request, visit the customer location, type a letter, analyze a forecast, negotiate a contract, create a new software program, fix a machine, or any of the million and one contributions we haven’t mentioned.”

Self-Managed Work Teams

Competent people with adequate information and tools often don’t need a boss constantly looking over their shoulder. Self-managed work teams are what the label implies—people who do their work collectively, without constant direction from a boss.

Watch It!

Teaming with colleagues from around the organization deeply bothers some people. They feel it infringes on the control they have over their work (or their departments). Some people also have trouble learning how to work with others. They only know how to do it themselves. News flash: With the world as complex as it has become, no person, work group, or department flies solo anymore. Teamwork is not just a business buzzword or fading fashion. Institutionalized collaboration is the way things are and are going to be.

Self-managed teams may:

- Propose or even determine their own budgets

- Hire and fire workers from the team

- Inspect their own work for quality

- Buy their own equipment or supplies

- Design their own work processes

Would you provide your 17-year-old daughter or son the keys to your car if they’d never been behind the wheel of any car before?

The same principle holds in putting workers in self-managed teams. It’s a great idea when:

- You have competent, experienced staff who can do the work without constant hand-holding

- The people on the team want to try the new method (pilot the concept with eager volunteers; people who resist the idea almost certainly will fail)

- The team members are eager to be educated to prepare for their new roles (communication, conflict management, planning, scheduling, or budgeting skills)

- Most importantly: you truly trust the people on the team and you really will let them operate independently—even when it’s not how you would have thought to do the job! Everyone must be held accountable and accept accountability for their actions.

Cross-Functional Not Dysfunctional

Today’s complex market forces companies to operate with tighter cycle times and constant innovation. In responding to these forces, many organizations have found that they need to get more parts of the company working with other parts more often (if not constantly).

At Your Service

Poorly performing teams sometimes fall short of their goals because team members aren’t properly educated on the impact their performance has on the entire team effort, both good and bad. Team members need to fully understand how and why their contribution is critical to the success of the team. They must also have a clear understanding of the negative impact they’d make if they do not follow through with their responsibilities. Without question, most human beings don’t want to be personally responsible for the defeat of their team. Make sure your team members understand the impact of their actions. Personal accountability goes a long way toward a gamewinning team performance.

You can have both temporary and ongoing cross-functional teams.

A temporary one might be assembled to solve a particular problem (why does this one account experience problems no one else seems to have), or seize an opportunity (what products or services might we offer to the growing segment of people who work out of their homes).

A standing cross-functional team may be one that serves assigned accounts. Members might represent several functional areas within your company, such as sales, product engineering, credit, customer care (the hip name for customer service departments these days), technical support, and so on.

Building a Successful Team

Here are some important factors to build in to the formula for successful cross-functional teams:

- Clearly-stated and fully-shared objectives

- Well-defined common measures of success

- Timely, full sharing of relevant information

- Adequate budgets, tools, and support systems to accomplish the objective

- A defined operating structure for the team (who can call meetings, how are decisions reached, how are disputes resolved?)

- Calling meetings only when necessary, for a specified amount of time, with an agenda distributed well in advance

- Individual performance evaluations tied to team participation and results

- Adherence to and acceptance of accountability

Is Your Perspective Correct?

Cross-functional and even intradepartmental work teams add more perspective and insight to any given business situation. The cliché is that two heads are better than one. And they are, when they’re both sharing ideas and information and building on the energy and creativity that naturally springs from a genuinely collaborative effort.

When choosing who should be on your team, the idea is to bring together a group of people who do not duplicate the efforts of others. Maximum team performance comes from individuals who each have something of value to bring to the table. It is the accumulation of all these values that results in achieving the overall objective. This is where the well known acronym comes from:

TEAM—Together Everyone Achieves More. If we knew who coined that phrase, we’d give her or him credit, for we could not have said it better ourselves.

Participating on a cross-functional team should not compete with someone’s “real job.” Team participation must be part of someone’s formal job description and performance review. We have talked to far to many people who felt that their boss either intentionally or inadvertently penalized them for their work on one or more teams.

Team assignments represent important work, and supervisors must fully support the people who participate in them—even when it causes a little inconvenience. This especially holds true for cross-functional team members who may be called on to report to another individual on a “dotted line” basis (reporting to someone on a temporary basis, or reporting to more than one boss) for a particular project. Without the support of the regular supervisor, the team member is likely to fall short in performing his team assignment.

The Least You Need to Know

- There is no perfect or recommended structure for running a customer service function.

- Working through teamwork is most successful when you know what kind of teamwork you mean. Specific tasks and your organization’s culture will drive the teamwork model you use.

- Self-managed teams can be wonderfully productive and save management overhead expenses when they’re adequately supported.

- Cross-functional teams help companies meet the challenges of change and competition. To be effective, they need to become part of the normal fabric of day-to-day operation.