Wheel of Life—Creating an in-camera multiple-exposure image like this one can require a great deal of collaboration between the model and the photographer. For this image, the model and I planned where she would be for each exposure. Then, when she was in position, I made the exposure using studio strobes. The camera was set to combine these multiple exposures. This is a modern take on an in-camera technique almost as old as photography itself.

In this image, the model worked with a hanging hoop called a lyre. Our plan was for her to work her way around the circle to create a wheel of humanity for the entire composition. Each time she moved into a new position, I pressed the remote shutter release and fired the strobes.

Nikon D800, 55mm Zeiss Otus, single in-camera multiple exposure with eight exposures, each exposure 1/160 of a second at f/9 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

Circles—and I use the term loosely to include ellipses and ovals—are compositionally powerful. But beware: relying on circles in your compositions can be dangerous.

Think of the way the language is used: A virtuous circle is a great thing, indicative of circular changes leading to improvement. In contrast, a vicious circle refers to a situation that just gets worse and worse.

Using a circle can be a visual trap. Once you are in the circle, how do you get out? What else is there to look at in the composition besides the circle?

These are true compositional dangers. But if you take the circle “by the horns” (so to speak) and embrace the peril along with the potentiality, circles can become an important part of the scaffolding that makes for compelling photography.

Backing up for a second, what exactly is the power of the circle?

Part of the power is that the eye is drawn to a circle in an image, particularly when the circle dominates the image. When you see a circle playing an important role in a photograph, it’s hard to look beyond the circle.

What are the other “power” characteristics of circles?

I’ve already mentioned that a circle can represent a closed system. In a closed system, the trends can be either good (virtuous) or bad (vicious).

Also keep in mind that a circle has no beginning and no end. This continuous nature of a circle is what makes virtuous and vicious feedback loops possible. Circularity also has other important consequences.

While there are sometimes exceptions, a circle often seems the same everywhere. Unlike shapes that are different when you rotate them, a circle rotated around its center point can still be just the same circle. This depends upon how symmetrical the circle is.

Another way of looking at circular geometry is that you can go around a circle forever. Think of the circle as a cosmic contribution to a virtual merry-go-round. Using circles in your photographic compositions adds a frisson of the amusement-park experience to your images.

When you make it back to the starting point of a circle, it’s time to begin again. Therefore, a circle can seem infinite. One way of thinking of this is to remember the classical motif of a serpent swallowing its own tail. There is no beginning, there is no end, and it goes on forever.

The idea of infinity is compelling enough. However, keep in mind that a circle can “drown out” all other shapes. When the eye sees a circle, nothing else may matter. The circle used in its broadest sense is such a compelling shape that it may preempt all other compositional gambits.

The danger in a composition involving a circle comes from the very potency of the shape (see “The Circle as Visual Archetype” on page 41). When a circle is present, who will think about, or look at, anything else?

Gran Via, Barcelona—To create this image, I made my way past a “do not enter” sign and onto the roof of an art deco hotel in Barcelona, Spain. It was nighttime in the autumn and the air was crisp.

I went to the edge of the roof and peered down on the traffic circle below. The fountain in the middle of the circle seemed to be changing colors. I thought the blue was the most interesting contrast with car taillights going by.

With this kind of photography, truly you have to “overshoot,” meaning it won’t be clear which exposure is best, or even if it works at all until you are able to evaluate after-the-fact. In this frame, I was happy with the way the patterns of car lights and arrows on the pavement balanced the power of the central circle in the composition. (Also, see discussion of this image on page 49.)

Nikon D810, 28-300mm Nikkor Zoom at 100mm, 5 seconds at f/13 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Portal—This image was intentionally created to evoke a fairy-tale portal into a different world. Within the fantastic world of the image, a decorative koi fish swims in a pond in front of a perfectly arched bridge. The bridge and its reflection form a circle. Passing through the circle is a distant landscape of a mountain lake in the late afternoon.

The three photographs that were used to create this Photoshop composite were photographed in (from front to back) a decorative fish pond in Kensington, California (the koi), the Hagiwara Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco (the bridge), and the Don Pedro Lake on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada in California (through the portal).

Koi Pond: Nikon D70, 18-70mm Nikkor Zoom at 70mm, circular polarizer, 1/100 of a second at f/5 and ISO 200, hand held.

Hagiwara Tea Garden: Nikon D300, 12-24mm Nikkor Zoom at 14mm, 1/200 of a second at f/8 and ISO 100, hand held.

Don Pedro Lake: Nikon D70, 18-70mm Nikkor Zoom at 20mm, 1/160 of a second at f/9 and ISO 200, hand held.

A circle, as in a mandala, can represent the entire world. Indeed, as you can see when you look closely at mandalas that go back into the deepest antiquity, a circle can also represent the entire universe. (To find out more about the mandala shape, turn to page 49.) So circles as shapes come with great symbolic meaning. Use a circle, use it well, but don’t use it heedlessly.

The trick in making successful imagery that includes a circular shape is to use the power of the circle as strength without falling for the pitfalls of circular entrapment.

It’s worth making the effort to learn how to accomplish compositional goals with circles. Some successful compositions that use circles do so by:

- Understanding the role of the circle as a visual archetype.

- Making the entire a composition about the circle, perhaps by creating an image where the circle performs as a complete and integral whole—for example, in a mandala.

- Playing with the viewer’s likely preconception about circles, and placing the circle off to one side.

- Making sure the circle is smaller than and balanced by other elements in the composition.

- Using the circle as a compositional doorway into another aspect of the composition, or indeed into an entire new world or universe.

The Circle as Visual Archetype

Carl Jung (1875–1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist whose multi-disciplinary work spanned psychology, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, and religion. One of Jung’s contributions involves understanding the importance of the archetype.

The idea of the archetype goes back to the beginnings of humanity’s ability to tell stories, and in visual art, perhaps as far back as the paintings on the walls of the caves at Lascaux (roughly 20,000 years ago). Jung’s ideas about archetypes were based in part on Plato’s conceptualization of the universal (or primordial) pattern (circa 400 BCE).

The Jungian archetype is a universal theme or symbol that resonates generally. People respond to the archetype, whether or not they recognize it consciously, in some cases across culture and time.

Archetypes at the level of the collective unconscious can be found in religious art, fairy tales, and mythology from around the world. Jung thought that archetypes existed independently of world events, current politics, and even the specifics of culture. In addition, the true archetype has influence throughout the stages of each individual’s unique development, although the way the archetype is perceived might vary from culture to culture, and between different individuals.

The study of archetypes is a large subject. However, it’s well worth the attention of any artist, because “plugging into” archetypes makes for images that tap into the collective unconscious, which is one of the broader and most important goals of art.

To the extent that an archetype is visually referenced, the composition will have greater resonance with the viewer. This is true whether or not the archetype is consciously recognized, and in fact, may be more effective when there is no conscious awareness of the reference to the archetype.

While this simplifies the composition (because there are additional horizontal lines), the cave entrance from within and its reflection form an ovoid. This oval shape matches the subject matter and evokes a portal to the sunlit world through the opening.

Entrance to Sơn Đoòng Cave—Sơn Đoòng Cave is located in the impenetrable mountainous jungles along the old Ho Chi Minh trail on the Vietnamese side of the Vietnam–Laos border. To get to the cave, you have to slog down a jungle mountainside, up a river bed, and through another vast cave into a hidden jungle valley. This is a difficult place to get to and is rarely visited.

To make this image, I used multiple-exposure HDR techniques to show both the inside of the cave and the jungle landscape outside. This is indeed a portal to a different world showing never-scaled heights, shafts of bright light, unusual flora, and perhaps the occasional jungle monkey descending on vines.

Nikon D810, 15mm Zeiss Distagon, eight exposures total: seven exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 0.6 of a second to 30 seconds, at f/22 and ISO 200; one exposure at 30 seconds at f/22 and ISO 500; tripod mounted.

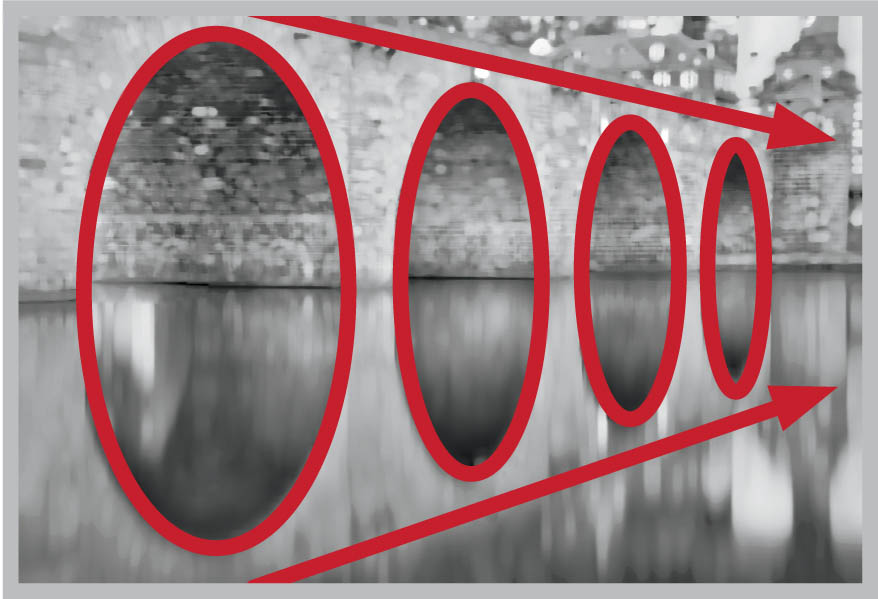

Alte Brücke, Heidelberg—One of Germany’s great rivers, the Neckar, flows through the university city of Heidelberg to its confluence with the Rhine River in Mannheim. The Romans built a bridge on the site of the Alte Brücke (“Old Bridge”). When floods swept the Roman bridge away, there was no crossing of the Neckar for over a millennia until the Alte Brücke was constructed in 1788.

I photographed the Alte Brücke at dusk, and used a neutral density filter. That way, I could make an exposure long enough (60 seconds) so the circles formed by the bridge arches and their reflections became a striking composition.

If you diagram the shapes in this composition, you’ll find successively smaller ovals. The converging perspective lines of the bridge and its reflection are almost tangent to the ovals. This is an attractive but somewhat complex composition taking advantage of the circularity of the bridge and reflections.

Nikon D800, 28-300 Nikkor Zoom at 90mm, +4 neutral density filter, 60 seconds at f/32 and ISO 50, tripod mounted.

Regardless of the theoretical Jungian framework of archetypes, when I look at a photograph that includes deep shadows I am aware at some level that the “dark side” of human nature is being referenced.

Keep in mind that archetypes usually work in a subliminal way. In other words, this can be a secret between the photographer and the viewer, and in some cases neither the photographer nor the viewer is actually aware of what is really going on with the archetype, even if they know that something is being touched at a deep level.

The viewer of your photo should not be saying to themselves, “Hey! That artist has tapped into an archetype!” Often the association of an image to the archetype is perceived unconsciously.

Art presents projective opportunities for adding personal assumptions to a universal symbol, in much the same way that a deck of Tarot cards provides symbolic characters and attributes that can be read in light of a personal situation.

Jung was himself a visual artist. Leaving aside the general validity of many of Jung’s ideas about the way the mind works, the concept of the visual archetype is important in photographic composition.

When it comes to visual archetypes, it is hard to think of any shape that is more fundamental than the circle. Indeed, if a composition strongly involves a circle, it is probably referencing an archetype. The circle as “world without end,” the circle as portal, the circle as wheel—one of the earliest, most important human inventions—and the mandala are some of the visual archetypes that are based on the circle.

Compositions That Are About the Circle

In its simplest form, the circle dominates the composition. In this kind of photograph, the composition is about the circle. Something is happening within the circle. A dancer moves around a ring or a flower gone to seed forms a bud. All, or most, of the action takes place within the circle.

For the photographer, it’s important to recognize a composition that is “about the circle” when it appears. Recognition of a composition that is about a circle will help you clear the frame of distractions and make the circle big, bold, and evident to the viewer.

Note that compositions that are about the circle often involve “squaring the circle.” In other words, a composition that is about the circle is usually bounded by a square, and may often be presented in a square crop.

The opposite can also be true. If a circular composition cannot be framed as a square, but fits better as a rectangle, then maybe you should put the circle aside and emphasize other aspects of your composition.

Putting the Circle Aside

What happens when you have a round composition that is almost circular? And what if other things besides the circle are going on?

Papaver Pod from Above—This photograph shows the dried pod of a Papaver somniferum, also known as the opium poppy. I mounted the poppy pod on a black velvet background using a straightened paper clip to keep it above the cloth.

To get as close to the poppy as you can see here, I used a macro lens and an extension tube.

To me, this botanical image looks a lot like a living creature, perhaps some form of starfish surrounded by a circle.

Nikon D850, 50mm Zeiss Makro-Planar, 24mm extension tube, five exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1 to 15 seconds, each exposure at f/22 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

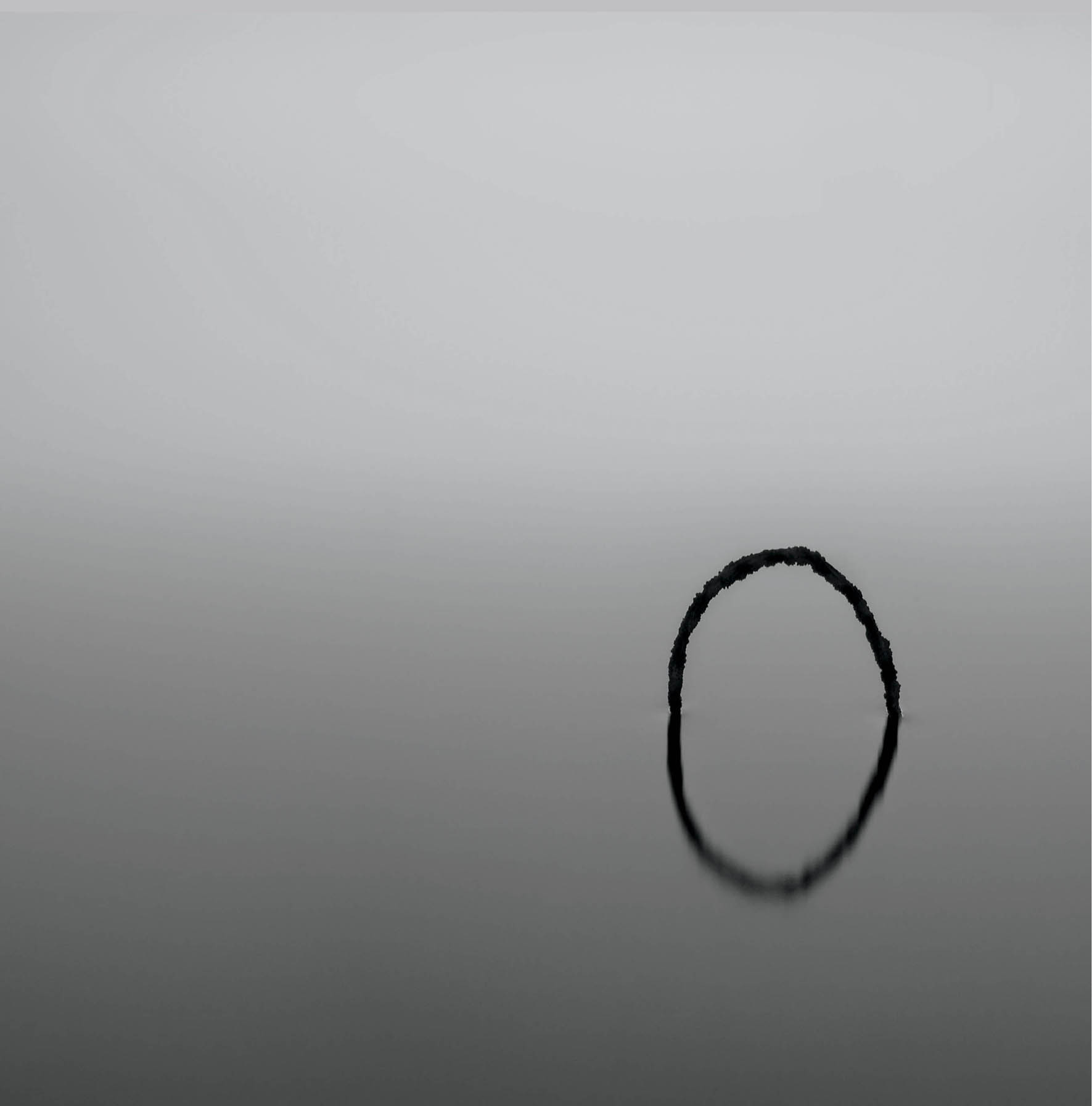

The Story of O—A generation ago, the landfill in San Francisco Bay adjacent to Albany, California, was filled with all kinds of junk. Yesterday’s junk is often today’s photographic opportunity.

I was walking along the muddy banks of the bay when I saw some rusted metal rebar poking up from the muck at the bottom of the bay. I realized that if I could use a long enough shutter speed and carefully slog through the mud to get to the right position, the rusted metal and its reflection would form a nearly perfect circle.

I used a +4 neutral density filter to make the exposure long enough (60 seconds) to soften the water.

Nikon D300, 18-200mm Nikkor Zoom at 35mm, +4 neutral density filter, 60 seconds at f/29 and ISO 100, tripod mounted.

It’s important to be able to step aside from the power of the circle and make the flourishes, lines, and shapes that are outside the circle important in their own right. A circle doesn’t always need to dominate!

An example of this kind of composition is the photograph of a traffic circle in Barcelona, shown on pages 38–39. This image was photographed from above at night. Certainly, the oval shape in the center of the composition—the fountain—is important. But that element could not stand on its own in the composition. Therefore, the cars in motion creating lighted swooshes “outside the circle” were significant and needed to be treated with care. When making the image, getting the balance of the car taillights was far more time consuming and difficult than centering the circular fountain.

Making the Most of Portals

A doorway into a different world—or a portal—is magical. Creating portals is one of the things I strive for in my photographic compositions.

While portals are not necessarily circular, many are composed of circles or ellipses (for example, check out the cave entrance in the photo on page 43).

It’s important when working with composition to take advantage of the suggestion of a magical portal. Other worlds can be good or bad, happy or sad, calm or apocalyptic. Whatever they are, alternate universes are fascinating and different. We look to portals to guide us in our lives in this world through their differences from our world, and to suggest what might possibly happen here in the future.

If the artist is a magician revealing what lies behind the shadows—and this is an important aspect of being an artist—showing portals is one of the most important tools of the trade. Emphasizing the presence of spiritual gateways in a photo is an easy and great way to show the possibility, as Leonard Cohen said, of a “crack where the light gets in.”

The Mandala Shape and the Magic of the Universe

In Eastern religions, a mandala may represent paradise, deities, or sacred spaces, or simply be used as an aid for meditation. The hallmark of a mandala is its circularity. Mandalas are always based on a circular shape. This helps explain why the mandala (and the circle) is one of the oldest shapes used for human artistic expression. The shape stands alone as a symbolic beginning without end, an end without a beginning.

Once you’ve embarked on a mandala, it’s often hard to integrate the circle of the mandala with an ordinary non-circular composition. Conversely, a rectilinear composition, such as a landscape, doesn’t usually merge easily or neatly into the infinite and endless possibilities conveyed by the swirling mandala.

So mandalas tend to be part of their own genre, and a thing unto themselves. It’s worth taking a hard look at the mandala for the purity of the circular shapes involved.

I’m not saying it is easy to construct mandalas using photography. In fact, this is a hard shape to integrate photographically; however, it is worth doing for the compositional exercise, and for the occasional extraordinary result.

My own mandalas are primarily created using flower petals on a light box (you can see one opposite), although of course I have used other materials as well. I’ve also experimented with cropping, and using a circular fisheye lens to create a mandala-like effect.

Your challenge is double-barreled: Try to learn about the power of the mandala so that this shape can be integrated into your own compositions. Then, practice creating images that consist entirely of a mandala.

It is worth learning about mandalas both in their art-historical context and in their usefulness as an adjunct to modern photographic composition. Creating successful photographic mandalas can be quite pleasing, and they will likely find an enthusiastic audience.

A Matter of Balance

In face of the overwhelming power of the circle as a compositional symbol, how do we find balance?

The answer, as in many things in life, involves clear communication. As a photographic artist, if you know that you have invoked the power of the circle, you should do so consciously. The fact that you are doing so with forethought by no means implies that the viewer of your image is aware of this.

Chasing Tails on Black—This image was constructed by placing alstroemeria (“Peruvian Lily”) petals on a light box. As I pieced together the composition, my idea was to echo the circular nature of a mandala. But it seemed to me that I could do something more by creating an echo of its infinite form. The title, Chasing Tails, refers to the idea that you can “enter” this composition from several different directions. (For more about entering and exiting composition, turn to page 139). But whatever way you choose to enter, you will soon be tangled in the endless loop of the mandala.

To finish the composition, I converted the white background to black in post-production using an LAB color inversion.

Nikon D850, 55mm Zeiss Otus, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/13 of a second to 2.5 seconds, each exposure at f/16 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Colored Apple Slices—To photograph apple slices on a light box, the first challenge is to slice the apple thinly. Very thinly! This is more of a challenge than may be at first apparent. The best tool is a mandolin, which is a vegetable slicer used in kitchens around the world. But the mandolin must be used with great delicacy; otherwise, the center of the apple will collapse.

Apples, in particular, appealed to my photographic eye because their slices can be almost perfect circles.

I liked the idea of creating a grid of evenly-spaced apple slices. This visual effect could be punctuation dots, botanical art, and wheels on a grander scale.

Looking at the slices on the white background of the light box, I realized that I had a great opportunity to play in postproduction. Manipulating colors using the LAB color space and Photoshop’s Blending Modes is one of my favorite pastimes.

To create this version of the image, I started by inverting the Lightness channel from white to black, so the apple slices would appear on a black background. Next, I created layer stacks with color manipulations using LAB channel variations.

This image shows an example of integrating circular shapes into a rectangular form using a grid as an organizational principle.

Nikon D850, 50mm Zeiss Makro-Planar, six exposures with shutter speeds ranging from 1/30 of a second to 1 second, each exposure at f/13 and ISO 64, tripod mounted.

Balance in circle compositions means either surrendering to the circle—acknowledging the circle as the key component of the composition—or complementing the circle with additional flourishes and swooshes that defy the centric nature of the circle.